Andreas Ervik on plants, bacteria and luxury in nature: Bring Your Own Plants and SANKE of Norway

[30/03/15]

BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014)

Andreas Ervik explores the multiple relationships between humans and ecologies at different levels of subjectivity. His projects are diverse, ranging from an arranged interspecies socialising for humans and their potted plants (Bring Your Own Plant) to glossy images of natural elements as the mock luxury brand, SANKE. Ervik reveals complex layers of communication between humans and nature by unmasking the science of minuscule ecosystems of microorganisms within our bodies and the thinking behind vast cultural habits of primitive and modern civilisations and their treatment of nature. Worm sits down with Andreas in Oslo to discuss his ideas and projects further:

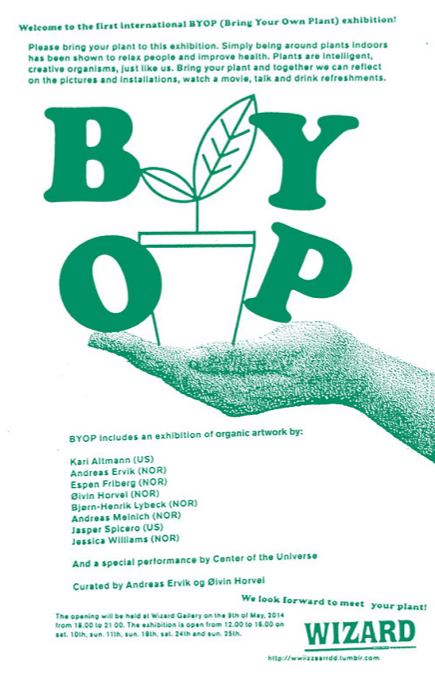

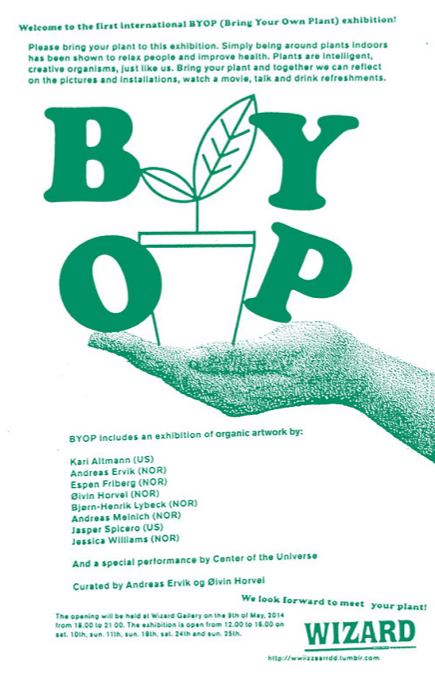

Hello Andreas! Your previous projects include BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014) in which you invited the public to bring their potted organisms to an exhibition you curated. To you, how do plants relate to one another as well as interact with ecologies outside their own?

I find it really interesting that plants are connected through networks of fungi in their root systems. Plants are interconnected, they exchange information. They have a way of being in the world, they sense and respond to the environment and interact with each other.

The way we usually relate to plants today is wish our pot plants, and not with the nature outside. We relate to our pot plants but they are disconnected from each other, completely cut off from the network of fungi, probably even depressed and lonely. And I have lots and lots of pot plants at home - it’s kind of sad to think about it. So I decided it would be nice to have a show bringing plants together, and putting emphasis on them as relational beings.

BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014)

The exhibition also came out of watching a BBC documentary called How Plants Communicate & Think, which is about plant intelligence. The intro describes how acacia trees, during a great drought, needed to protect their scarce leaves from over-grassing. The trees have a poisonous substance in the leaves, and as animals were grassing on them the trees sent pheromones, as a message to the surrounding trees to increase the poison as well. As the animals grassed they got more and more poison in their systems, which eventually killed them. The trees had killed the animals in order to survive! From this, I’ve been very interested in this idea of plants as active.

BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014)

Despite this attempt to liberate houseplants by bringing them into human social events, it still restricts them from real interaction and embodies the human desire to control nature’s role in our world. Tell us about SANKE of Norway, your most recent project, which furthers these ideas to incorporate the commodification of nature.

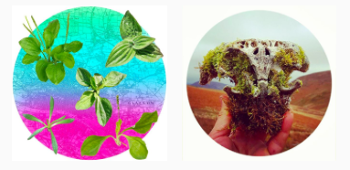

SANKE is a luxury health-brand, focusing on products based in evolutionary principles. As a luxury brand it can create a desire for nature. The products are really expensive, which maxes out exclusivity, but also adds absurdity. One product is a single chocolate, filled with soil, and the price is $70. Another is a bottle of unfiltered river water, which costs $150. It is insane to pay that large amount of money for something made out of natural ingredients, which you can just go and find yourself. This realisation can possibly generate a sentiment that these things have great value. That soil, water, trees, plants actually are luxurious elements. So the project is about commodification, but it also raises environmental concerns.

SANKE jord 2015

In your recent talk in Oslo at Atelier Nord ANX, you introduced SANKE’s intention as “To use nature like branded goods, as an extension of the body”. What does SANKE hold as an art project constructed as a luxury brand?

As a luxury brand it focuses on beauty and attraction, making things for desire. I found it interesting to combine that with the idea of nature, because nature is now something we feel we have grown out of. In our daily life we rarely interact with plants, trees and animals in the ways that humans did until just a few generations ago. We live in cities, spending our time using technologies and focusing on branded objects. At best nature is a backdrop, somewhere we go to take selfies. In this context I wanted to use the strategies and techniques from marketing to make nature feel important.

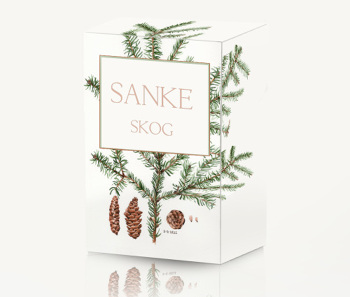

The brand name, SANKE, is the Norwegian word for gathering. It was inspired by the ancient practice of engaging with the environment – gathering what is in season, preparing and eating or conserving it. The products have Norwegian names as well, and the ones launched so far are skog (forest), elv (river) and jord (soil, or earth). Making these products, and the ones that are coming, I reprioritize my own activities, spending more time outside, and filling my online presence with natural elements.

SANKE skog 2015

This intimacy between humans and nature is dependent on that people’s “Lust for hygiene and fear of bacteria” be dissolved. Your solution offers nature through the aesthetics of cosmetic advertisements. How does this destabilize the assumptions of nature as thriving ecologies of organisms, with consumers in preference for a pure, packaged and clinical nature?

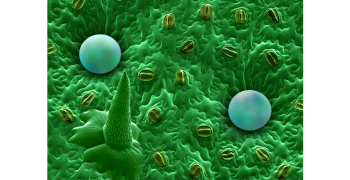

I don’t want to destabilise the idea of nature as thriving ecologies in this sense. It’s quite the opposite – I’m interested in the shift of what constitutes humans, from individual subjectivity and thinking to ecologies of co-inhabiting microorganisms. The bacteria and viruses that make up the human ecology shape and influence us in crucial ways. The bacteria in our gut for instance influence our moods and they produce the serotonin, aka the happiness hormone, whereby determining whether we feel bad or good. This is important in the presentation of SANKE jord, the soil-filled chocolate and SANKE elv, unfiltered river water. I have displaced the notion of human subjectivity and agency with this idea that microorganisms have created us in order to further themselves and we are merely vessels of bacteria and microorganisms.

SANKE elv 2015

When most people think of microbes, though, they think of disease and lack of hygiene. For instance, media tells us how people now send text messages while on the toilet, portraying this as extremely dangerous, and that the smartphones should be sanitised. These are horror stories, attesting a contemporary desire to escape the body, with its disgusting materiality of faeces, urine, menstruation and semen, and disease-bearing pathogens. We want to escape the primal parts of being human; to purify ourselves and become more like the technologies, the products and what is presented to us through marketing. A major part of SANKE is how I can hijack this, sneaking in the disgusting elements of filth, bacteria, soil and the dirty into what is desirable.

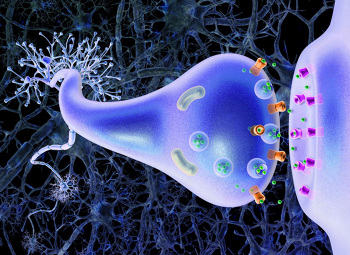

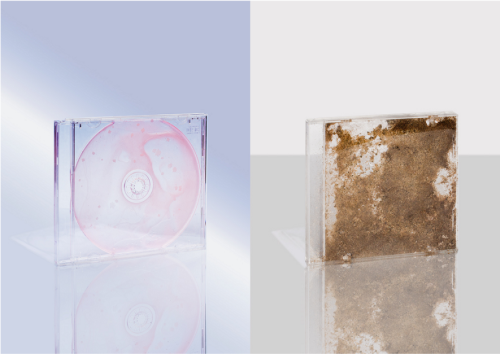

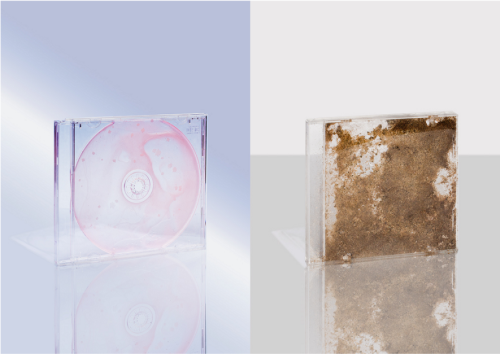

CDCD, 2012. For the exhibition Revision Arts 02: Metamorphosis (December 2012), the artist has been exploring human relationships with technology and with microorganisms

Bruce Sterling ironically comments on how parts of contemporary society grasp global climate change issues and tackles them through a cultural phenomenon. He commentates that “Fashion is talking about climate change because that is tomorrow’s issue”. Furthermore, he praises fashion’s self-augmentation to challenge green views. “(Political) Greens preach in grimy, condescending pamphlets such as One Hundred Ways to Save the Plant, while Vogue actually assembles and manipulates public opinion”.

With SANKE trying to be like a luxury brand with its particular products, and is mimicking the marketing strategies of the very specialised, very eco-minded products, then maybe it comes as no surprise that SANKE is rather trendy.

How do you relate yourself as an artist working within undoubtedly “trendy” aesthetic and how do you follow discourses towards a constructive output, which survive fleeting trends? To further this, how does one combat the fleeting trendiness of such a topic, of culturally fashionable images, and the day-to-day trendiness of vegetarianism and recycling? How do you see trends and active productivity and production?

There really is some truth in the notion that environmentalists have these unwanted and annoying messages that people don’t really want to hear, while someone like Vogue delivers stuff that is beautiful and attractive.

Yesterday I was looking at images in interior decoration magazines. It’s something I often do for inspiration, because they use objects much like artists do in installations today. The texts in these magazine are usually shallow and horrible, but there was one where the designer said something like, “I don’t like working with fleeting trends, I want to work with something permanent” and the journalist added, “There’s nothing trendier right now than doing something permanent”. That encapsulates something I really like.

Trendiness isn’t necessarily a bad thing. To reach people you need to hit upon trends in some way. I think that it is really weird to talk about this in relation to SANKE and even to BYOP, because I’m really not that good at spotting trends. With BYOP, I only just realised that I was being trendy when a journalist told me in an interview. To me it is interesting and bizarre because I have a hard time understanding how popular culture works much of the time. I’m not good at predicting these things.

Andreas Ervik

Your line of SANKE offers “Ancestral Harvest” as a line of products derived from ancient knowledge on natural health benefits. How have these qualities been appropriated in contemporary consumerism? How do you divulge in alternatives in primitivism and anti-civilisation movements?

My use of terms such as ancestral harvest and primal nature ties in with current tendencies, such as for instance the primal movement. There’s some great stuff coming out of that, and I’m a big fan in particular of the writing of Mark Sisson.

Some portray it as apolitical and nostalgic, but I think this misses the potentially revolutionary impact. Sisson writes about the importance of re-wilding the planet and ourselves – playing more, spending time with kids, changing eating patterns for a sustainable planet and working bodies. These interventions might seem obvious, but I think that just like environmentalists can learn a lot from marketing, critical theorists can learn a lot from health fads. The primal movement is a sort of utopian project. Instead of criticising our current situation and making people feel bad about themselves, it instigates change by making it seem possible.

The biggest health problems facing people in the West today are the diseases of civilisation: heart disease, dementia, and alzheimer, at least some of the cancers, schizophrenia, autoimmunity, allergies, obesity, asthma and depression, and many more. It’s a long, long list, and all of these are results of civilisation, diseases that didn’t exist before. They are rarely discussed as results of civilisation, though, and are mostly presented as genetic mysteries. Most of them seem, however, not to be entirely genetic. The diseases are instead consequences of shifts in the human micro-flora, which has been taking place since the advent of civilisation, and have escalated in modernity. The microorganisms that should keep our immune systems, bodies and mental health working properly have gone missing from many of us, due to our excessive hygiene, antibiotic use, the modern diet and the lack of contact with nature and animals. The primal movement seeks to restore these problems, and the SANKE brand has grown out of this thinking.

SANKE skog 2015

All images are Andreas Ervik’s, except for the BYOP flyer by Espen Friberg.

---

Follow Andreas Ervik:

Website: www.andreaservik.com

Soundcloud: andreaservik

Tumblr: www.andreaservik.tumblr.com

Twitter: @sankeofnorway

Instagram:@sankeofnorway

SANKE of Norway

Bring Your Own Plant

BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014)

Andreas Ervik explores the multiple relationships between humans and ecologies at different levels of subjectivity. His projects are diverse, ranging from an arranged interspecies socialising for humans and their potted plants (Bring Your Own Plant) to glossy images of natural elements as the mock luxury brand, SANKE. Ervik reveals complex layers of communication between humans and nature by unmasking the science of minuscule ecosystems of microorganisms within our bodies and the thinking behind vast cultural habits of primitive and modern civilisations and their treatment of nature. Worm sits down with Andreas in Oslo to discuss his ideas and projects further:

Hello Andreas! Your previous projects include BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014) in which you invited the public to bring their potted organisms to an exhibition you curated. To you, how do plants relate to one another as well as interact with ecologies outside their own?

I find it really interesting that plants are connected through networks of fungi in their root systems. Plants are interconnected, they exchange information. They have a way of being in the world, they sense and respond to the environment and interact with each other.

The way we usually relate to plants today is wish our pot plants, and not with the nature outside. We relate to our pot plants but they are disconnected from each other, completely cut off from the network of fungi, probably even depressed and lonely. And I have lots and lots of pot plants at home - it’s kind of sad to think about it. So I decided it would be nice to have a show bringing plants together, and putting emphasis on them as relational beings.

BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014)

The exhibition also came out of watching a BBC documentary called How Plants Communicate & Think, which is about plant intelligence. The intro describes how acacia trees, during a great drought, needed to protect their scarce leaves from over-grassing. The trees have a poisonous substance in the leaves, and as animals were grassing on them the trees sent pheromones, as a message to the surrounding trees to increase the poison as well. As the animals grassed they got more and more poison in their systems, which eventually killed them. The trees had killed the animals in order to survive! From this, I’ve been very interested in this idea of plants as active.

BYOP (Bring Your Own Plant, 2014)

Despite this attempt to liberate houseplants by bringing them into human social events, it still restricts them from real interaction and embodies the human desire to control nature’s role in our world. Tell us about SANKE of Norway, your most recent project, which furthers these ideas to incorporate the commodification of nature.

SANKE is a luxury health-brand, focusing on products based in evolutionary principles. As a luxury brand it can create a desire for nature. The products are really expensive, which maxes out exclusivity, but also adds absurdity. One product is a single chocolate, filled with soil, and the price is $70. Another is a bottle of unfiltered river water, which costs $150. It is insane to pay that large amount of money for something made out of natural ingredients, which you can just go and find yourself. This realisation can possibly generate a sentiment that these things have great value. That soil, water, trees, plants actually are luxurious elements. So the project is about commodification, but it also raises environmental concerns.

SANKE jord 2015

In your recent talk in Oslo at Atelier Nord ANX, you introduced SANKE’s intention as “To use nature like branded goods, as an extension of the body”. What does SANKE hold as an art project constructed as a luxury brand?

As a luxury brand it focuses on beauty and attraction, making things for desire. I found it interesting to combine that with the idea of nature, because nature is now something we feel we have grown out of. In our daily life we rarely interact with plants, trees and animals in the ways that humans did until just a few generations ago. We live in cities, spending our time using technologies and focusing on branded objects. At best nature is a backdrop, somewhere we go to take selfies. In this context I wanted to use the strategies and techniques from marketing to make nature feel important.

The brand name, SANKE, is the Norwegian word for gathering. It was inspired by the ancient practice of engaging with the environment – gathering what is in season, preparing and eating or conserving it. The products have Norwegian names as well, and the ones launched so far are skog (forest), elv (river) and jord (soil, or earth). Making these products, and the ones that are coming, I reprioritize my own activities, spending more time outside, and filling my online presence with natural elements.

SANKE skog 2015

This intimacy between humans and nature is dependent on that people’s “Lust for hygiene and fear of bacteria” be dissolved. Your solution offers nature through the aesthetics of cosmetic advertisements. How does this destabilize the assumptions of nature as thriving ecologies of organisms, with consumers in preference for a pure, packaged and clinical nature?

I don’t want to destabilise the idea of nature as thriving ecologies in this sense. It’s quite the opposite – I’m interested in the shift of what constitutes humans, from individual subjectivity and thinking to ecologies of co-inhabiting microorganisms. The bacteria and viruses that make up the human ecology shape and influence us in crucial ways. The bacteria in our gut for instance influence our moods and they produce the serotonin, aka the happiness hormone, whereby determining whether we feel bad or good. This is important in the presentation of SANKE jord, the soil-filled chocolate and SANKE elv, unfiltered river water. I have displaced the notion of human subjectivity and agency with this idea that microorganisms have created us in order to further themselves and we are merely vessels of bacteria and microorganisms.

SANKE elv 2015

When most people think of microbes, though, they think of disease and lack of hygiene. For instance, media tells us how people now send text messages while on the toilet, portraying this as extremely dangerous, and that the smartphones should be sanitised. These are horror stories, attesting a contemporary desire to escape the body, with its disgusting materiality of faeces, urine, menstruation and semen, and disease-bearing pathogens. We want to escape the primal parts of being human; to purify ourselves and become more like the technologies, the products and what is presented to us through marketing. A major part of SANKE is how I can hijack this, sneaking in the disgusting elements of filth, bacteria, soil and the dirty into what is desirable.

CDCD, 2012. For the exhibition Revision Arts 02: Metamorphosis (December 2012), the artist has been exploring human relationships with technology and with microorganisms

Bruce Sterling ironically comments on how parts of contemporary society grasp global climate change issues and tackles them through a cultural phenomenon. He commentates that “Fashion is talking about climate change because that is tomorrow’s issue”. Furthermore, he praises fashion’s self-augmentation to challenge green views. “(Political) Greens preach in grimy, condescending pamphlets such as One Hundred Ways to Save the Plant, while Vogue actually assembles and manipulates public opinion”.

With SANKE trying to be like a luxury brand with its particular products, and is mimicking the marketing strategies of the very specialised, very eco-minded products, then maybe it comes as no surprise that SANKE is rather trendy.

How do you relate yourself as an artist working within undoubtedly “trendy” aesthetic and how do you follow discourses towards a constructive output, which survive fleeting trends? To further this, how does one combat the fleeting trendiness of such a topic, of culturally fashionable images, and the day-to-day trendiness of vegetarianism and recycling? How do you see trends and active productivity and production?

There really is some truth in the notion that environmentalists have these unwanted and annoying messages that people don’t really want to hear, while someone like Vogue delivers stuff that is beautiful and attractive.

Yesterday I was looking at images in interior decoration magazines. It’s something I often do for inspiration, because they use objects much like artists do in installations today. The texts in these magazine are usually shallow and horrible, but there was one where the designer said something like, “I don’t like working with fleeting trends, I want to work with something permanent” and the journalist added, “There’s nothing trendier right now than doing something permanent”. That encapsulates something I really like.

Trendiness isn’t necessarily a bad thing. To reach people you need to hit upon trends in some way. I think that it is really weird to talk about this in relation to SANKE and even to BYOP, because I’m really not that good at spotting trends. With BYOP, I only just realised that I was being trendy when a journalist told me in an interview. To me it is interesting and bizarre because I have a hard time understanding how popular culture works much of the time. I’m not good at predicting these things.

Andreas Ervik

Your line of SANKE offers “Ancestral Harvest” as a line of products derived from ancient knowledge on natural health benefits. How have these qualities been appropriated in contemporary consumerism? How do you divulge in alternatives in primitivism and anti-civilisation movements?

My use of terms such as ancestral harvest and primal nature ties in with current tendencies, such as for instance the primal movement. There’s some great stuff coming out of that, and I’m a big fan in particular of the writing of Mark Sisson.

Some portray it as apolitical and nostalgic, but I think this misses the potentially revolutionary impact. Sisson writes about the importance of re-wilding the planet and ourselves – playing more, spending time with kids, changing eating patterns for a sustainable planet and working bodies. These interventions might seem obvious, but I think that just like environmentalists can learn a lot from marketing, critical theorists can learn a lot from health fads. The primal movement is a sort of utopian project. Instead of criticising our current situation and making people feel bad about themselves, it instigates change by making it seem possible.

The biggest health problems facing people in the West today are the diseases of civilisation: heart disease, dementia, and alzheimer, at least some of the cancers, schizophrenia, autoimmunity, allergies, obesity, asthma and depression, and many more. It’s a long, long list, and all of these are results of civilisation, diseases that didn’t exist before. They are rarely discussed as results of civilisation, though, and are mostly presented as genetic mysteries. Most of them seem, however, not to be entirely genetic. The diseases are instead consequences of shifts in the human micro-flora, which has been taking place since the advent of civilisation, and have escalated in modernity. The microorganisms that should keep our immune systems, bodies and mental health working properly have gone missing from many of us, due to our excessive hygiene, antibiotic use, the modern diet and the lack of contact with nature and animals. The primal movement seeks to restore these problems, and the SANKE brand has grown out of this thinking.

SANKE skog 2015

All images are Andreas Ervik’s, except for the BYOP flyer by Espen Friberg.

---

Follow Andreas Ervik:

Website: www.andreaservik.com

Soundcloud: andreaservik

Tumblr: www.andreaservik.tumblr.com

Twitter: @sankeofnorway

Instagram:@sankeofnorway

SANKE of Norway

Bring Your Own Plant