TJ Demos on the exhibition Rights of Nature and his forthcoming book Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology

[01/03/15]

Rights of Nature at Nottingham Contemporary, 24 Jan 2015 - 15 Mar 2015. Photo Nottingham Contemporary

Rights of Nature: Art and Ecology in the Americas is the current major exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, UK, which investigates art and the politics of ecology of North and South America. The show destabilises passivity towards global environmental issues, including urgent economic, political and ecological problems that are results of neoliberal overconsumption. It gathers twenty artists and specifically substantiates awareness, rethinks justice and energises action for both the nature and the indigenous people of the Americas given their historical marginalisation since European colonisation. Rights of Nature is curated by Professor TJ Demos and Dr. Alex Farquharson, with Irene Aristizábal.

TJ Demos is an art writer and critic on contemporary art and politics. In addition to numerous books and notable essays in various journals, TJ Demos guest-edited a special issue of Third Text (no. 120, January 2013) titled “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology". He has been a Reader at University College London and has now begun his professorship at University of California Santa Cruz, directing the Centre for Creative Ecologies. Worm warmly invites TJ Demos to speak more about Rights of Nature and his forthcoming book Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology.

Hello TJ, Worm is very excited about your new show Rights of Nature at Nottingham Contemporary. To begin with, how would you define the title of the exhibition, specifically what is ‘nature’ as opposed to ‘ecology’ and how does your choice of wording relate to the philosophies of Félix Guattari, Bruno Latour, and Timothy Morton?

Rights of nature refers most directly to the legal revolution taking place around the world right now, which has been building momentum over the last couple decades, for instance, since the publication of Michel Serres’ The Natural Contract in 1990. Serres claimed that we humans (from so-called developed countries in the West) have been at war with nature since the Enlightenment, if not antiquity, and that we are entering an age when the Earth will no longer passively accept our destructive ways without making life difficult for us. His answer was to propose a new natural contract that would equalize the playing field by moving us beyond an anthropocentric relation to the environment. That philosophical insight has paralleled a transformation in legal jurisprudence which has recognized the rights of nature in courts of law, so that nature is no longer viewed merely as property and its value defined solely in terms of its usefulness to humans. Rather, in what’s called Earth jurisprudence, or Wild Law, we witness a biocentric redefinition of nature’s rights that accord intrinsic value to nonhuman life forms and environmental systems—including the right to subsist in a state undisturbed by human destructiveness.

With the publication of books by the South African environmental lawyer Cormac Cullinan (including his 2002 book Wild Law), the biocentric philosophy of “geologian” Thomas Berry, and even earlier legal precedents (such as Christopher D. Stone’s 1972 paper “Should Trees have [legal] Standing?”), there has been huge steps forward in implementing the rights of nature in international courts. Most specifically, this implementation has been realized in the constitutions and legal systems of Ecuador and Bolivia as of 2008, countries that have seen energetic Indigenous movements mobilize in support of different forms of life other than the ones outlined by the corporate globalization of neoliberal capitalism.

In this regard, rights of nature is embedded in the cosmopolitics of Indigenous philosophy and legal codes, especially, in the Latin American context, and in the Andean Amerindian philosophy of “sumak kawsay,” Quichua for “buen vivir” or “living well.” Buen vivir describes a form of life based in collective egalitarianism (of living well, but not “better” than one’s neighbor), and extends the legal and political “community” to the nonhuman realm of animals and ecosystems. In other words, buen vivir defines a strong commitment to environmental biodiversity and living according to a natural equilibrium that is ecologically sustainable—far from the development doctrines of Western “free market” capitalism, which favor economic growth above all else.

Minerva Cuevas, Serie Hidrocarburos, 2007

Our exhibition at Nottingham has attempted to locate artistic practices situated across the Americas that respond to this biocentric legal, philosophical, and ecological revolution, via a diversity of approaches and positions. In relation to the work of Guattari, Latour, and Morton, there’s a number of complex relations. Many of the works, for example, attempt to differentiate and complicate the notion of ecology in the way Guattari theorized—in terms of what he called the “three ecologies” of psychology, sociability, and environment, which urgently required reformatting to escape from the unsustainability of “world integrated capitalism”. Perhaps the greatest difference with the more recent authors you mention—Latour and Morton—is that the show’s conceptualization refuses to surrender the term “nature,” as it is a crucial rallying cry in the rights of nature movement. While I would agree that “nature” needs a theoretical rearticulation—so that it’s no longer describing a pure zone apart from the human, or an ideological manoeuvre that “naturalizes” historical and cultural knowledge, as Latour and Morton warn against—we don’t need to give up entirely on the term.

What’s needed is a conceptual reinvention, and this occurs with rights of nature discourse. In addition, our exhibition project acknowledges the very important contributions of Indigenous knowledge and philosophy in the formulation of the rights of nature, which is a mark of its more recent articulation (this is apparent in Cullinan’s work, but not really in the environmental ethics of Roderick Nash’s seminal 1990 book The Rights of Nature). In this regard, I’m sensitive to the critiques of speculative realism, new materialism, and object-oriented ontology coming from Indigenous scholars such as Zoe Todd and Kim TallBear, who argue that non-Indigenous scholars in the Western academy (like Jane Bennett and Latour) tend to continue the systematic exclusion of Indigenous cosmologies in their theorizations of “vital matter,” “cosmopolitics,” and “nonhuman agency,” cosmologies that have long possessed their own theorizations of the natural world that have had nothing to do with the West’s longstanding colonization of nature. By including Indigenous artists and referencing Indigenous voices, our exhibition has attempted to approach these questions in very different ways than Guattari, Latour, and Morton.

Extending this definition to ‘rights’, the exhibition spans the Americas and brings together the concerns of environmentalism and post-colonialism, climate and social justice, in order to expose European exploitation of America’s natural resources and its indigenous people. Does nature hold intrinsic rights to the same extent as humans? How are those involved in the show using art to highlight history, inequalities and activism to fight for nature’s right to have rights, alongside the rights of Indigenous people?

Foremost amongst the principles of Earth jurisprudence is the recognition that all members of the planet’s community possess legal rights, including the right to exist and participate in the evolution of life’s biodiverse networks of interdependent systems. But the focus is not so much on the rights of individual subjects—as if a chicken could sue a fox in a court of law for violating its rights by attempting to eat it! Rather, rights of nature attempt to protect the integrity of systems, in which we find carnivorous food chains among others. It’s only when biodiversity is threatened, along with the integrity of eco-systems, that there is a problem. One of the cutting-edge developments in this form of legality is the International Rights of Nature Tribunal, which includes leading proponents such as Indian eco-activist Vandana Shiva, South African environmental lawyer Cormac Cullinan, Ecuadoran Kichwa leader Blanca Chancoso, Ecuadoran economist Alberto Acosta, and Tom Goldtooth of the Diné/Dakota nations, among others. Their goal is to enact hearings on violations of rights of nature in order to provide a template to states and the international community so that one can visualize how such a legal system could be enacted within governance systems. To date, they have held hearings against Condor Mirador Mining in Ecuador, BP’s 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Belo Monte Dam project in Brazil, Chevron-Texaco activities in Ecuador, oil drilling in Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park, and hydraulic fracturing in Argentina. These offer a good sense of just what rights of nature is directed against.

Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, Forest Law, video, 2014. Photo artists.

In our exhibition, the contribution that comes closest to investigating rights of nature is Forest Law by Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, a video installation project that investigates the history of oil drilling and environmental destruction in the Ecuadoran Amazon. They look at how Indigenous peoples, including the Serayaku and the Shuar, have taken recourse in courts of law (such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights), to hold corporations like Texaco responsible for leaving massive areas of forest floor contaminated with toxic extraction residues, which threaten the forest’s biodiversity and Indigenous livelihood in the area. The piece also offers an overview of rights of nature in Ecuador, showing how rights of nature legislation emerged from the struggles for Indigenous justice that began in the early 1990s, with the formation of CONAIE, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, and that in the present situation in Ecuador, Earth jurisprudence remains very precarious, as the country’s president, Rafael Correa, has paid lip-service to rights of nature (facilitating the constitution’s amendment in 2008), even while he lends his support to a series of extractivist projects at the same time, such as drilling in Yasuni National Park. Biemann and Tavares provide an account of this complex historical and geopolitical situation, which is also philosophically expressive of Indigenous views that it is ultimately the Earth itself that defines the rights that we must all learn to respect; if not, our very survival is jeopardized. Bringing rights of nature into our legal constitutions is one way of aligning human civilization with the planet’s living systems. At the same time, the biopolitical implications of this development are far from simple or uncontested, which Forest Law reveals.

The Native American activist, environmentalist and writer, Winoa LaDuke, once said, “I think there are more European fairy tales about going off and personally becoming happy than there are about bringing corn to your community or bringing the gift of wild rice or bringing the drum or the pipe”[1]. I feel this resonates with how Rights of Nature also reveals the return to indigenous cultures as those most knowledgeable and caring to nature and other beings, as opposed to the capitalistic and neoliberal mistreatments, which are challenged throughout the show. How do some of the artists and groups you have included in your exhibition emphasise the value of cultural identity and community commitment?

There are a number of responses in the show that emphasize these values. One is the work of Fernando Palma, a Nahua artist based near Mexico City, who has contributed a large sculptural installation comprised of robotic butterflies that move in elegant patterns according to the logic boards that he has constructed with his DIY electronics. Palma explains that in traditional Nahua culture, there is no such word as “rubbish,” an absence that indicates how traditionally held recycling practices have long existed in this community, even while those practices were corroded in the post-colonial period. Nonetheless, it is industrial waste—such as the aluminium cans used in soft drinks with which he constructs his butterflies—that is threatening fragile habitats, including that of the Monarch butterfly. These insects have a sanctuary outside of Mexico City, and they travel as far as Canada over a year-long multigenerational migration. But in recent years their population has crashed, owing to the use of chemical fertilizers and GM monocrops in industrial agribusiness landscapes. Palma effectively reanimates butterflies that are threatened with extinction, doing so in a way that reflects both his culture’s respect for the dignity of nonhuman agents (considered “persons”), and the causal conditions of habitat destruction (including the habitat of Indigenous people) located within an industrial culture of waste, homogenization, and capitalist irresponsibility.

Fernando Palma Rodríguez, Techpactia tlen quipanoz ipan Milpa Alta? (Do you like what happens in Milpa Alta?), 2011 and Tocihuapapalutzin (Our revered lady butterfly), 2009. Courtesy the artist. Photo Andy Keate.

Another example from our show is the work of GIAP, or Grupo de Investigación en Arte y Política, who have contributed an archive of Zapatista visual culture, one that visualizes and reinforces the Chiapas-based struggle for Indigenous sovereignty, anti-globalization self-sufficiency, and sustainable agroecology. The archive includes the political prints of Escuela de Cultura Popular Mártires del ’68 (ECPM68), and the colorful paintings by Beatriz Aurora that depict traditional Mayan cultural practices (such as organic gardening of heritage corn varieties) mixed with revolutionary forms of life. Whereas Forest Law invokes rights of nature as the object of activist constitutionalism carried out in courts of law (and thereby depends on partially unreliable political systems for legal enforcement, which have been inconsistent at best), the Zapatistas have gained their own geographical autonomy and instituted their own legal codes beyond the rule of the Mexican state and its support for NAFTA’s chemical-intensive and GM-based agribusiness (the North American Free Trade Agreement is an early version of TTIP, currently under consideration in Europe, which threatens increased corporate power and destruction of food sovereignty). NAFTA was signed in 1994, the same year that the Zapatistas rose in opposition to the threats to their sovereignty, traditional ways of life, and cultural survival. They remain one of the most important models of a localist, egalitarian, and ecologically sustainable cultural practice on a collective scale, which is also rooted in Indigenous traditions as much as in postmodern high-tech communication networks, and as such we found it crucial to include reference to their revolutionary work in Rights of Nature.

World of Matter is an international project you have written about before and, relating to Mabe Bethônico’s research and work on mining and minerals,Anselm Jappe’s text underlines the anthropocentric possession of nature. He states, “Capitalism is not a production of goods for the purpose of meeting needs. Rather, it seeks value, and this value is, since antiquity, in precious metals”[2]. How does Rights of Nature challenge this valuation of natural resources, which survives on greedy biopiracy and corporate ownership of natural resources?

In our exhibition, we didn’t want to focus so much on enviro-pessimism, meaning giving full rein to yet another presentation of contemporary catastrophism, which we’re fed so steadily in the mass media. Think of all the post-apocalyptic and zombie films that Hollywood spews out on a regular basis—as if we’re addicted to observing our own disastrous future repeatedly in spectacular form, as if that’s the only future we can possibly entertain. That catastrophism is the endpoint of translating nature into natural resource, as purely instrumentalized value existing only for human consumption. That said, there is a piece by the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Rights of Nature that portrays what happens to the planet in such conditions. Their video, The Houston Petrochemical Corridor Landscan, depicts Houston’s shows the incredible expansiveness of the city’s oil’s refinery infrastructure via a slow aerial pan that unfolds over 14 minutes. It presents a colonization of nature that shows the fossil fuel industry as a necropolitical machine of ecocide.

The Center for Land Use Interpretation, Houston Petrochemical Corridor Landscan, 2008. Courtesy of The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

Nonetheless our aim has been to present projects that are committed to bringing about a shift in perspective toward a valuation of nature that is post- or non-capitalist, where nature is not a resource to be consumed, but possesses an intrinsic value that is non-anthropocentric. This is made clear in the “Universal Declaration of Rights of Mother Earth,” adopted in 2010 at the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and proposed to the UN where it is currently under consideration. Among its central articles, we find the following: “Mother Earth is a unique, indivisible, self-regulating community of interrelated beings that sustains, contains and reproduces all beings” and that “the inherent rights of Mother Earth are inalienable in that they arise from the same source as existence.” What would it mean to perceive nature as such, how would it shift our relation to the world around us and to ourselves? This is what a number of projects in our exhibition do in creating a paradigm-shift in our cosmopolitical understanding of the world.

One great example is the photography, writing and activism of Subhankar Banerjee, who presents a cycle of images in Rights of Nature that shows the majesty of the Arctic as a place of fragile biodiversity, supporting the migration patterns of caribou and snow geese as much as the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples like the Gwich’in (a micro-minority First Nation living in Alaska and Canada’s Northwest Territories). Against US oil interest in the area, especially under the administration of George W. Bush, which intended to open up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to exploration and cynically claimed that the North was only a “vast white nothingness,” Banerjee’s photography brings aesthetic sensibility to Earth’s “unique, indivisible, self-regulating community of interrelated beings,” which animates a politics of reverence that contests the greedy extractivism of the fossil-fuel industry.

Yet Banerjee’s work is far from an us-versus-them argument, and he would be the first to point out that all of us are dependent to some degree on conventional energy currently for our contemporary lives (in terms of the carbon footprint made in transporting his photographs to Nottingham as much as the Gwich’in’s use of snowmobiles in their hunting practices). The more complex point of his work, in my view, is to explore the intertwined ecologies—biopolitical as well as climatological, postmodern and Indigenous as much as anthropogenic and non-anthropocentric—of this precarious habitat, which exists on the forefront of environmental policy. Indeed, how we decide to collectively value this nature in the present will foreshadow our society’s fate in the future.

Subhankar Banerjee shows eight photographs of Arctic Alaska from the permanent collection of Lannan Foundation. Photo Nottingham Contemporary

The exhibition press release comments that Bolivia and Ecuador now have new environmental laws, and, as you mentioned, many of the works deal with the commodification of natural resources and the discussion of its legalities, notably Ursuala Biemann and Paulo Tavares’ Forest Law. Here in Norway, a small set of artists and researchers are reinstating the 1814 Constitution’s clause 112[3], which declares the obligation of the state to take care of the environment for future generations. However, in these two hundred years, the clause has become forgotten, overshadowed by its booming oil industry, and is little known outside environmental groups in Norway. In your view, how much of a role can the law, and those who stand for it (Indigenous people/artists/activists/environmentalists), truly have over safeguarding nature in the Americas and elsewhere in the world?

In Ecuador and Bolivia as well, there has been a mixed record of implementing the rights of nature in a meaningful way, as I mentioned above. There is thus far more work to do before such Earth law is able to radically change the course of modern development and its growth-obsessed economies. However, rights of nature legislation is making headway, which is clearly analyzed in the critical literature. What we’ve found in our research for the Nottingham exhibition is that the work of Indigenous groups, environmental activists, and engaged citizens are and will be crucial to advance the rights of nature in a direction where environmental policy is no longer determined by corporate interests, where there is a profound reassessment of the growth economy and its bankrupt system of value, and where a different ecocentric form of sustainability becomes possible and realizable. Also, there may be a difference in orientation of current rights of nature, as compared to the laws of Norway’s constitution. Although I’m no expert on Norwegian environmental law, I suspect that the clause you mention also fits into the paradigm of asserting natural protections in order to safeguard human (economic) development, rather than developing the rights of nature beyond such anthropocentric perspectives.

While this may seem an academic theoretical distinction, it is in fact an important difference and could help redirect current modes of governance away from the hegemony of industrial interests that has belied past environmental protections. On the other hand, perhaps current rights of nature will be more easily adopted in those countries that do have an important history of environmental protection, even if it’s been largely formal and inconsistently applied in the past. In this regard, the rights of nature movement is no finished ecological project; rather it’s an ongoing legal revolution driven by social movements that continue to struggle to get global governance to support its effective realization.

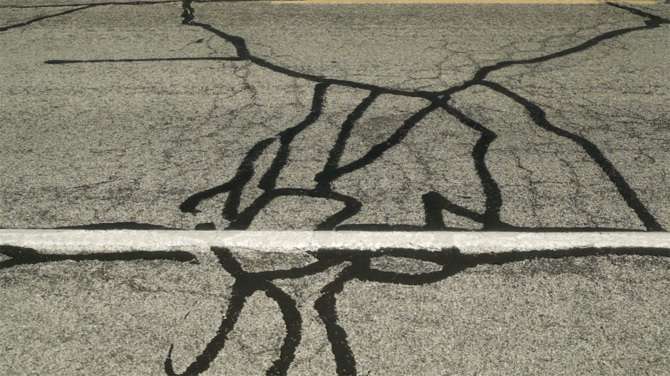

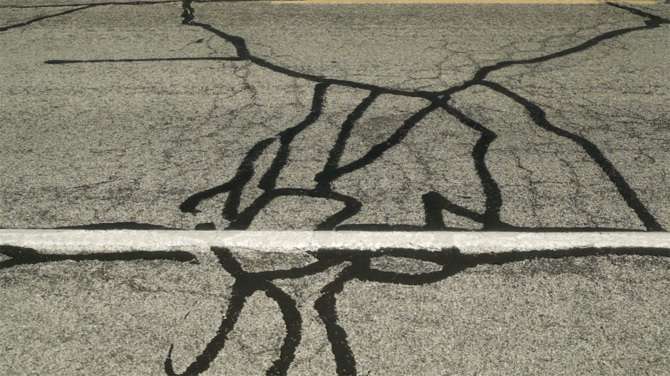

The Otolith Group, Medium Earth, HD video, UK, 2013. Courtesy of The Otolith Group and LUX, London.

The Rights of Nature International Conference coincided with the opening of the exhibition, which was broadcasted live online. Tackling the difficultly in-depth and scientific language of official UN climate change reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Amy Balkin’s performance piece Reading the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (2009) took place throughout the day of the conference. Considering the crucial role the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report will play this year for Paris COP21, how does such esoteric language become accessible to those who may be deterred from participating in ecological discussions? Does the language and needs of grassroots environmental activism and climate justice for indigenous people alter in the framework of different institutions, be it the UN or major art galleries?

Amy’s IPCC reading went really well at the conference. Read by local activists (including those against fracking in the UK), it occurred in the midst of the auditorium during the opening and breaks of the conference, and I referred to it also in my opening remarks—this is all archived online and available for free streaming. I thought her piece was a very provocative intervention in the day’s discussions, entering somewhere between a crucial registration of the scientific consensus around anthropogenic climate change and the manifold threats that it poses to life as we know it; and an insightful reflection on how such specialist-sourced information can fail to reach non-specialist people in the busy dealings of everyday life. In other words, it posed some of the central challenges of dealing with political ecology today! While some critics would argue that the IPCC is quite centrist owing to its methodological basis in consensus science, and to some even politically irresponsible as a result, it’s crucial to have this science in relation to the current battle with the fossil-fuel industry and the governments that support their interests, to the detriment of our climate and future viability of life.

Still, it’s also imperative to translate that language into one that people can understand and relate to, to situate it within creative and affective forms that hold the potential to move people, raise consciousness, and alter perspectives, on levels other than the scientific-informational, and diverse artistic and cultural languages hold exactly that potential. Grassroots activism and climate justice campaigns have long attempted to contest UN governance, especially given that the UN is so undemocratic and hierarchical, where powerful states can exert a disproportionate influence on the formulation of policy (the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, for example, is planning as we speak for interventions at COP21 in Paris). Were the UN to democratize, so that one country would get one vote, for instance, the world would immediately be a different place!

Amy Balkin, Public Smog, Video, 2004-2014. Courtesy of the Artist.

In relation to the rights of nature, one necessary legal mechanism that has yet to be put into place is the governance of enforcement, so that Earth jurisprudence is not merely an abstract legal idealism. For instance, if ecocide were made a criminal offence, so that corporations could be held accountable for their destructive activities, and their CEOs and directors held criminally responsible as well, then this would give rights of nature the teeth needed for its principles to be realized globally, as activists are calling for (see the work of environmental lawyer Polly Higgins for example in support of enshrining ecocide in the law).

Art galleries are no doubt quite modest in their potential to effect change; however, they can add to the momentum of social movements, transform the perspective of visitors in quite powerful ways, and pose questions and model alternatives that can add to the creativity needed to address environmental crisis. At our conference, for instance, Eriel Deranger, of the of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation of Alberta, Canada, spoke about the current Tar Sands industrial project to extract dirty oil in what is an incredibly destructive venture, one that has also impacted Indigenous peoples living in the area, subjecting them to atrocious human health ailments and ruining their environment. UK-based anti-fracking groups (such as Frack Free Nottinghamshire) were also present at the conference, and there were many impassioned discussions between environmental and Indigenous activists, politically engaged artists, cultural theorists, and students at the event—exactly the kind of intersectionalist politics (a politics built of movements of movements), that we need to expand the conversation, invite more people to join the struggle, and create transnational alliances. It is such a politics that will transform the world, and art galleries (when divorced from their dedication to commercial fetishism and presenting a depoliticized aesthetics of the 1%) can play an integral role in the formation of political engagement and creative thinking—the ingredients of world-making, or cosmopolitics, to which Rights of Nature connects.

Lastly, what are the issues that you discuss and analyse in your forthcoming book, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology? When will the book be available

The book—available from Sternberg Press in later 2015—broadly investigates how concern for ecological crisis has entered the field of contemporary art and visual culture in recent years. While ecology has received little systematic attention within art history (not surprising, given its longstanding basis in humanism), ecology’s visibility and significance has only grown worldwide in relation to the pressing threats of climate change, global warming and the environmental destruction of ecosystems. To address these imperatives, this book considers creative proposals from speculative realist and new materialist philosophy, Indigenous cosmopolitics, climate justice activism, and Earth law as critical resources for how to model just forms of life that bring together ecological sustainability, postcapitalist politics, and radical democracy, at a time when those proposals are needed more than ever. By engaging artists’ widespread aesthetic and political engagement of environmental conditions and processes, and doing so in relation to an expansive global scope of investigations—looking at developments in the global South as much as the North—this book offers what I hope will be a significant contribution to the intersecting fields of art history, ecology, visual culture, geography, and environmental politics.

Decolonizing Nature is organized both thematically (with chapters that critically address subjects such as climate refugees, the politics of sustainability, the financialization of nature, and contemporary catastrophism) and geographically (with additional chapters or sections dedicated to Mexico, India, the Arctic, and small island nations like the Maldives, in addition to the US and Europe). Even so, the material has proved so complex that I think of the book now as an introduction to future research. Now that I’ve moved to University of California Santa Cruz, I’ll be able to pursue this work more directly than in London, and I’ll also direct the Center for Creative Ecologies at UCSC, which proposes to offer a platform from which to consider the intersection of culture and environment. The aim is to formulate research tools with which to examine how cultural practitioners—filmmakers, new media strategists, photojournalists, architects, writers, activists, and interdisciplinary theorists—critically address and creatively negotiate environmental concerns. These concerns include anthropogenic climate change and global warming, and relate to factors such as habitat destruction, drought, species extinction, and environmental degradation. Drawing on such wide-ranging fields as political ecology and degrowth economics, Earth jurisprudence and new materialism philosophy, Indigenous cosmologies and climate justice, the Center intends to create a place for the formation of the emerging environmental arts and humanities. But it’s quite early days, and you’ll need to check back in a year or so to see where we’re at!

Marcos Avila Forero, A Tarapoto, Un Manati, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Dohyang Lee, Paris.

---

The artists included in this exhibition are: Allora & Calzadilla, Eduardo Abaroa, Ala Plástica, Darren Almond, Marcos Avila Forero, Amy Balkin, Subhankar Banerjee, Mabe Bethônico, Ursula Biemann & Paulo Tavares, Center for Land Use Interpretation, Minerva Cuevas, Jimmie Durham, Harun Farocki, GIAP: Grupo de Investigación en Arte y Política (with Beatriz Aurora), Paulo Nazareth, The Otolith Group, Fernando Palma Rodríguez, Claire Pentecost, Abel Rodríguez, Miguel Angel Rojas, Walter Solón Romero.

The images are from Nottingham Contemporary and the artists.

Notes:

[1] Winoa Laduke, interviewed by Paul Schmelzer, How the Land Lies: Omaa aikiing in Land, Art: Ecology Handbook

[2] Anselm Jeppe, World of Matter http://www.worldofmatter.net/mineral-exploitation-i#path=mineral-exploitation-i

[3] Klimafestivalen, Norway, December 2014– January 2015 http://klimafestivalen112.no/grunnlovens-§112/

---

Follow the writer TJ Demos online at UCSC UCSC

Listen to the discussion at Demos' book launch at The Showroom here.

Rights of Nature at Nottingham Contemporary, 24 Jan 2015 - 15 Mar 2015. Photo Nottingham Contemporary

Rights of Nature: Art and Ecology in the Americas is the current major exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, UK, which investigates art and the politics of ecology of North and South America. The show destabilises passivity towards global environmental issues, including urgent economic, political and ecological problems that are results of neoliberal overconsumption. It gathers twenty artists and specifically substantiates awareness, rethinks justice and energises action for both the nature and the indigenous people of the Americas given their historical marginalisation since European colonisation. Rights of Nature is curated by Professor TJ Demos and Dr. Alex Farquharson, with Irene Aristizábal.

TJ Demos is an art writer and critic on contemporary art and politics. In addition to numerous books and notable essays in various journals, TJ Demos guest-edited a special issue of Third Text (no. 120, January 2013) titled “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology". He has been a Reader at University College London and has now begun his professorship at University of California Santa Cruz, directing the Centre for Creative Ecologies. Worm warmly invites TJ Demos to speak more about Rights of Nature and his forthcoming book Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology.

Hello TJ, Worm is very excited about your new show Rights of Nature at Nottingham Contemporary. To begin with, how would you define the title of the exhibition, specifically what is ‘nature’ as opposed to ‘ecology’ and how does your choice of wording relate to the philosophies of Félix Guattari, Bruno Latour, and Timothy Morton?

Rights of nature refers most directly to the legal revolution taking place around the world right now, which has been building momentum over the last couple decades, for instance, since the publication of Michel Serres’ The Natural Contract in 1990. Serres claimed that we humans (from so-called developed countries in the West) have been at war with nature since the Enlightenment, if not antiquity, and that we are entering an age when the Earth will no longer passively accept our destructive ways without making life difficult for us. His answer was to propose a new natural contract that would equalize the playing field by moving us beyond an anthropocentric relation to the environment. That philosophical insight has paralleled a transformation in legal jurisprudence which has recognized the rights of nature in courts of law, so that nature is no longer viewed merely as property and its value defined solely in terms of its usefulness to humans. Rather, in what’s called Earth jurisprudence, or Wild Law, we witness a biocentric redefinition of nature’s rights that accord intrinsic value to nonhuman life forms and environmental systems—including the right to subsist in a state undisturbed by human destructiveness.

With the publication of books by the South African environmental lawyer Cormac Cullinan (including his 2002 book Wild Law), the biocentric philosophy of “geologian” Thomas Berry, and even earlier legal precedents (such as Christopher D. Stone’s 1972 paper “Should Trees have [legal] Standing?”), there has been huge steps forward in implementing the rights of nature in international courts. Most specifically, this implementation has been realized in the constitutions and legal systems of Ecuador and Bolivia as of 2008, countries that have seen energetic Indigenous movements mobilize in support of different forms of life other than the ones outlined by the corporate globalization of neoliberal capitalism.

In this regard, rights of nature is embedded in the cosmopolitics of Indigenous philosophy and legal codes, especially, in the Latin American context, and in the Andean Amerindian philosophy of “sumak kawsay,” Quichua for “buen vivir” or “living well.” Buen vivir describes a form of life based in collective egalitarianism (of living well, but not “better” than one’s neighbor), and extends the legal and political “community” to the nonhuman realm of animals and ecosystems. In other words, buen vivir defines a strong commitment to environmental biodiversity and living according to a natural equilibrium that is ecologically sustainable—far from the development doctrines of Western “free market” capitalism, which favor economic growth above all else.

Minerva Cuevas, Serie Hidrocarburos, 2007

Our exhibition at Nottingham has attempted to locate artistic practices situated across the Americas that respond to this biocentric legal, philosophical, and ecological revolution, via a diversity of approaches and positions. In relation to the work of Guattari, Latour, and Morton, there’s a number of complex relations. Many of the works, for example, attempt to differentiate and complicate the notion of ecology in the way Guattari theorized—in terms of what he called the “three ecologies” of psychology, sociability, and environment, which urgently required reformatting to escape from the unsustainability of “world integrated capitalism”. Perhaps the greatest difference with the more recent authors you mention—Latour and Morton—is that the show’s conceptualization refuses to surrender the term “nature,” as it is a crucial rallying cry in the rights of nature movement. While I would agree that “nature” needs a theoretical rearticulation—so that it’s no longer describing a pure zone apart from the human, or an ideological manoeuvre that “naturalizes” historical and cultural knowledge, as Latour and Morton warn against—we don’t need to give up entirely on the term.

What’s needed is a conceptual reinvention, and this occurs with rights of nature discourse. In addition, our exhibition project acknowledges the very important contributions of Indigenous knowledge and philosophy in the formulation of the rights of nature, which is a mark of its more recent articulation (this is apparent in Cullinan’s work, but not really in the environmental ethics of Roderick Nash’s seminal 1990 book The Rights of Nature). In this regard, I’m sensitive to the critiques of speculative realism, new materialism, and object-oriented ontology coming from Indigenous scholars such as Zoe Todd and Kim TallBear, who argue that non-Indigenous scholars in the Western academy (like Jane Bennett and Latour) tend to continue the systematic exclusion of Indigenous cosmologies in their theorizations of “vital matter,” “cosmopolitics,” and “nonhuman agency,” cosmologies that have long possessed their own theorizations of the natural world that have had nothing to do with the West’s longstanding colonization of nature. By including Indigenous artists and referencing Indigenous voices, our exhibition has attempted to approach these questions in very different ways than Guattari, Latour, and Morton.

Extending this definition to ‘rights’, the exhibition spans the Americas and brings together the concerns of environmentalism and post-colonialism, climate and social justice, in order to expose European exploitation of America’s natural resources and its indigenous people. Does nature hold intrinsic rights to the same extent as humans? How are those involved in the show using art to highlight history, inequalities and activism to fight for nature’s right to have rights, alongside the rights of Indigenous people?

Foremost amongst the principles of Earth jurisprudence is the recognition that all members of the planet’s community possess legal rights, including the right to exist and participate in the evolution of life’s biodiverse networks of interdependent systems. But the focus is not so much on the rights of individual subjects—as if a chicken could sue a fox in a court of law for violating its rights by attempting to eat it! Rather, rights of nature attempt to protect the integrity of systems, in which we find carnivorous food chains among others. It’s only when biodiversity is threatened, along with the integrity of eco-systems, that there is a problem. One of the cutting-edge developments in this form of legality is the International Rights of Nature Tribunal, which includes leading proponents such as Indian eco-activist Vandana Shiva, South African environmental lawyer Cormac Cullinan, Ecuadoran Kichwa leader Blanca Chancoso, Ecuadoran economist Alberto Acosta, and Tom Goldtooth of the Diné/Dakota nations, among others. Their goal is to enact hearings on violations of rights of nature in order to provide a template to states and the international community so that one can visualize how such a legal system could be enacted within governance systems. To date, they have held hearings against Condor Mirador Mining in Ecuador, BP’s 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Belo Monte Dam project in Brazil, Chevron-Texaco activities in Ecuador, oil drilling in Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park, and hydraulic fracturing in Argentina. These offer a good sense of just what rights of nature is directed against.

Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, Forest Law, video, 2014. Photo artists.

In our exhibition, the contribution that comes closest to investigating rights of nature is Forest Law by Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, a video installation project that investigates the history of oil drilling and environmental destruction in the Ecuadoran Amazon. They look at how Indigenous peoples, including the Serayaku and the Shuar, have taken recourse in courts of law (such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights), to hold corporations like Texaco responsible for leaving massive areas of forest floor contaminated with toxic extraction residues, which threaten the forest’s biodiversity and Indigenous livelihood in the area. The piece also offers an overview of rights of nature in Ecuador, showing how rights of nature legislation emerged from the struggles for Indigenous justice that began in the early 1990s, with the formation of CONAIE, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, and that in the present situation in Ecuador, Earth jurisprudence remains very precarious, as the country’s president, Rafael Correa, has paid lip-service to rights of nature (facilitating the constitution’s amendment in 2008), even while he lends his support to a series of extractivist projects at the same time, such as drilling in Yasuni National Park. Biemann and Tavares provide an account of this complex historical and geopolitical situation, which is also philosophically expressive of Indigenous views that it is ultimately the Earth itself that defines the rights that we must all learn to respect; if not, our very survival is jeopardized. Bringing rights of nature into our legal constitutions is one way of aligning human civilization with the planet’s living systems. At the same time, the biopolitical implications of this development are far from simple or uncontested, which Forest Law reveals.

The Native American activist, environmentalist and writer, Winoa LaDuke, once said, “I think there are more European fairy tales about going off and personally becoming happy than there are about bringing corn to your community or bringing the gift of wild rice or bringing the drum or the pipe”[1]. I feel this resonates with how Rights of Nature also reveals the return to indigenous cultures as those most knowledgeable and caring to nature and other beings, as opposed to the capitalistic and neoliberal mistreatments, which are challenged throughout the show. How do some of the artists and groups you have included in your exhibition emphasise the value of cultural identity and community commitment?

There are a number of responses in the show that emphasize these values. One is the work of Fernando Palma, a Nahua artist based near Mexico City, who has contributed a large sculptural installation comprised of robotic butterflies that move in elegant patterns according to the logic boards that he has constructed with his DIY electronics. Palma explains that in traditional Nahua culture, there is no such word as “rubbish,” an absence that indicates how traditionally held recycling practices have long existed in this community, even while those practices were corroded in the post-colonial period. Nonetheless, it is industrial waste—such as the aluminium cans used in soft drinks with which he constructs his butterflies—that is threatening fragile habitats, including that of the Monarch butterfly. These insects have a sanctuary outside of Mexico City, and they travel as far as Canada over a year-long multigenerational migration. But in recent years their population has crashed, owing to the use of chemical fertilizers and GM monocrops in industrial agribusiness landscapes. Palma effectively reanimates butterflies that are threatened with extinction, doing so in a way that reflects both his culture’s respect for the dignity of nonhuman agents (considered “persons”), and the causal conditions of habitat destruction (including the habitat of Indigenous people) located within an industrial culture of waste, homogenization, and capitalist irresponsibility.

Fernando Palma Rodríguez, Techpactia tlen quipanoz ipan Milpa Alta? (Do you like what happens in Milpa Alta?), 2011 and Tocihuapapalutzin (Our revered lady butterfly), 2009. Courtesy the artist. Photo Andy Keate.

Another example from our show is the work of GIAP, or Grupo de Investigación en Arte y Política, who have contributed an archive of Zapatista visual culture, one that visualizes and reinforces the Chiapas-based struggle for Indigenous sovereignty, anti-globalization self-sufficiency, and sustainable agroecology. The archive includes the political prints of Escuela de Cultura Popular Mártires del ’68 (ECPM68), and the colorful paintings by Beatriz Aurora that depict traditional Mayan cultural practices (such as organic gardening of heritage corn varieties) mixed with revolutionary forms of life. Whereas Forest Law invokes rights of nature as the object of activist constitutionalism carried out in courts of law (and thereby depends on partially unreliable political systems for legal enforcement, which have been inconsistent at best), the Zapatistas have gained their own geographical autonomy and instituted their own legal codes beyond the rule of the Mexican state and its support for NAFTA’s chemical-intensive and GM-based agribusiness (the North American Free Trade Agreement is an early version of TTIP, currently under consideration in Europe, which threatens increased corporate power and destruction of food sovereignty). NAFTA was signed in 1994, the same year that the Zapatistas rose in opposition to the threats to their sovereignty, traditional ways of life, and cultural survival. They remain one of the most important models of a localist, egalitarian, and ecologically sustainable cultural practice on a collective scale, which is also rooted in Indigenous traditions as much as in postmodern high-tech communication networks, and as such we found it crucial to include reference to their revolutionary work in Rights of Nature.

World of Matter is an international project you have written about before and, relating to Mabe Bethônico’s research and work on mining and minerals,Anselm Jappe’s text underlines the anthropocentric possession of nature. He states, “Capitalism is not a production of goods for the purpose of meeting needs. Rather, it seeks value, and this value is, since antiquity, in precious metals”[2]. How does Rights of Nature challenge this valuation of natural resources, which survives on greedy biopiracy and corporate ownership of natural resources?

In our exhibition, we didn’t want to focus so much on enviro-pessimism, meaning giving full rein to yet another presentation of contemporary catastrophism, which we’re fed so steadily in the mass media. Think of all the post-apocalyptic and zombie films that Hollywood spews out on a regular basis—as if we’re addicted to observing our own disastrous future repeatedly in spectacular form, as if that’s the only future we can possibly entertain. That catastrophism is the endpoint of translating nature into natural resource, as purely instrumentalized value existing only for human consumption. That said, there is a piece by the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Rights of Nature that portrays what happens to the planet in such conditions. Their video, The Houston Petrochemical Corridor Landscan, depicts Houston’s shows the incredible expansiveness of the city’s oil’s refinery infrastructure via a slow aerial pan that unfolds over 14 minutes. It presents a colonization of nature that shows the fossil fuel industry as a necropolitical machine of ecocide.

The Center for Land Use Interpretation, Houston Petrochemical Corridor Landscan, 2008. Courtesy of The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

Nonetheless our aim has been to present projects that are committed to bringing about a shift in perspective toward a valuation of nature that is post- or non-capitalist, where nature is not a resource to be consumed, but possesses an intrinsic value that is non-anthropocentric. This is made clear in the “Universal Declaration of Rights of Mother Earth,” adopted in 2010 at the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and proposed to the UN where it is currently under consideration. Among its central articles, we find the following: “Mother Earth is a unique, indivisible, self-regulating community of interrelated beings that sustains, contains and reproduces all beings” and that “the inherent rights of Mother Earth are inalienable in that they arise from the same source as existence.” What would it mean to perceive nature as such, how would it shift our relation to the world around us and to ourselves? This is what a number of projects in our exhibition do in creating a paradigm-shift in our cosmopolitical understanding of the world.

One great example is the photography, writing and activism of Subhankar Banerjee, who presents a cycle of images in Rights of Nature that shows the majesty of the Arctic as a place of fragile biodiversity, supporting the migration patterns of caribou and snow geese as much as the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples like the Gwich’in (a micro-minority First Nation living in Alaska and Canada’s Northwest Territories). Against US oil interest in the area, especially under the administration of George W. Bush, which intended to open up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to exploration and cynically claimed that the North was only a “vast white nothingness,” Banerjee’s photography brings aesthetic sensibility to Earth’s “unique, indivisible, self-regulating community of interrelated beings,” which animates a politics of reverence that contests the greedy extractivism of the fossil-fuel industry.

Yet Banerjee’s work is far from an us-versus-them argument, and he would be the first to point out that all of us are dependent to some degree on conventional energy currently for our contemporary lives (in terms of the carbon footprint made in transporting his photographs to Nottingham as much as the Gwich’in’s use of snowmobiles in their hunting practices). The more complex point of his work, in my view, is to explore the intertwined ecologies—biopolitical as well as climatological, postmodern and Indigenous as much as anthropogenic and non-anthropocentric—of this precarious habitat, which exists on the forefront of environmental policy. Indeed, how we decide to collectively value this nature in the present will foreshadow our society’s fate in the future.

Subhankar Banerjee shows eight photographs of Arctic Alaska from the permanent collection of Lannan Foundation. Photo Nottingham Contemporary

The exhibition press release comments that Bolivia and Ecuador now have new environmental laws, and, as you mentioned, many of the works deal with the commodification of natural resources and the discussion of its legalities, notably Ursuala Biemann and Paulo Tavares’ Forest Law. Here in Norway, a small set of artists and researchers are reinstating the 1814 Constitution’s clause 112[3], which declares the obligation of the state to take care of the environment for future generations. However, in these two hundred years, the clause has become forgotten, overshadowed by its booming oil industry, and is little known outside environmental groups in Norway. In your view, how much of a role can the law, and those who stand for it (Indigenous people/artists/activists/environmentalists), truly have over safeguarding nature in the Americas and elsewhere in the world?

In Ecuador and Bolivia as well, there has been a mixed record of implementing the rights of nature in a meaningful way, as I mentioned above. There is thus far more work to do before such Earth law is able to radically change the course of modern development and its growth-obsessed economies. However, rights of nature legislation is making headway, which is clearly analyzed in the critical literature. What we’ve found in our research for the Nottingham exhibition is that the work of Indigenous groups, environmental activists, and engaged citizens are and will be crucial to advance the rights of nature in a direction where environmental policy is no longer determined by corporate interests, where there is a profound reassessment of the growth economy and its bankrupt system of value, and where a different ecocentric form of sustainability becomes possible and realizable. Also, there may be a difference in orientation of current rights of nature, as compared to the laws of Norway’s constitution. Although I’m no expert on Norwegian environmental law, I suspect that the clause you mention also fits into the paradigm of asserting natural protections in order to safeguard human (economic) development, rather than developing the rights of nature beyond such anthropocentric perspectives.

While this may seem an academic theoretical distinction, it is in fact an important difference and could help redirect current modes of governance away from the hegemony of industrial interests that has belied past environmental protections. On the other hand, perhaps current rights of nature will be more easily adopted in those countries that do have an important history of environmental protection, even if it’s been largely formal and inconsistently applied in the past. In this regard, the rights of nature movement is no finished ecological project; rather it’s an ongoing legal revolution driven by social movements that continue to struggle to get global governance to support its effective realization.

The Otolith Group, Medium Earth, HD video, UK, 2013. Courtesy of The Otolith Group and LUX, London.

The Rights of Nature International Conference coincided with the opening of the exhibition, which was broadcasted live online. Tackling the difficultly in-depth and scientific language of official UN climate change reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Amy Balkin’s performance piece Reading the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (2009) took place throughout the day of the conference. Considering the crucial role the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report will play this year for Paris COP21, how does such esoteric language become accessible to those who may be deterred from participating in ecological discussions? Does the language and needs of grassroots environmental activism and climate justice for indigenous people alter in the framework of different institutions, be it the UN or major art galleries?

Amy’s IPCC reading went really well at the conference. Read by local activists (including those against fracking in the UK), it occurred in the midst of the auditorium during the opening and breaks of the conference, and I referred to it also in my opening remarks—this is all archived online and available for free streaming. I thought her piece was a very provocative intervention in the day’s discussions, entering somewhere between a crucial registration of the scientific consensus around anthropogenic climate change and the manifold threats that it poses to life as we know it; and an insightful reflection on how such specialist-sourced information can fail to reach non-specialist people in the busy dealings of everyday life. In other words, it posed some of the central challenges of dealing with political ecology today! While some critics would argue that the IPCC is quite centrist owing to its methodological basis in consensus science, and to some even politically irresponsible as a result, it’s crucial to have this science in relation to the current battle with the fossil-fuel industry and the governments that support their interests, to the detriment of our climate and future viability of life.

Still, it’s also imperative to translate that language into one that people can understand and relate to, to situate it within creative and affective forms that hold the potential to move people, raise consciousness, and alter perspectives, on levels other than the scientific-informational, and diverse artistic and cultural languages hold exactly that potential. Grassroots activism and climate justice campaigns have long attempted to contest UN governance, especially given that the UN is so undemocratic and hierarchical, where powerful states can exert a disproportionate influence on the formulation of policy (the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, for example, is planning as we speak for interventions at COP21 in Paris). Were the UN to democratize, so that one country would get one vote, for instance, the world would immediately be a different place!

Amy Balkin, Public Smog, Video, 2004-2014. Courtesy of the Artist.

In relation to the rights of nature, one necessary legal mechanism that has yet to be put into place is the governance of enforcement, so that Earth jurisprudence is not merely an abstract legal idealism. For instance, if ecocide were made a criminal offence, so that corporations could be held accountable for their destructive activities, and their CEOs and directors held criminally responsible as well, then this would give rights of nature the teeth needed for its principles to be realized globally, as activists are calling for (see the work of environmental lawyer Polly Higgins for example in support of enshrining ecocide in the law).

Art galleries are no doubt quite modest in their potential to effect change; however, they can add to the momentum of social movements, transform the perspective of visitors in quite powerful ways, and pose questions and model alternatives that can add to the creativity needed to address environmental crisis. At our conference, for instance, Eriel Deranger, of the of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation of Alberta, Canada, spoke about the current Tar Sands industrial project to extract dirty oil in what is an incredibly destructive venture, one that has also impacted Indigenous peoples living in the area, subjecting them to atrocious human health ailments and ruining their environment. UK-based anti-fracking groups (such as Frack Free Nottinghamshire) were also present at the conference, and there were many impassioned discussions between environmental and Indigenous activists, politically engaged artists, cultural theorists, and students at the event—exactly the kind of intersectionalist politics (a politics built of movements of movements), that we need to expand the conversation, invite more people to join the struggle, and create transnational alliances. It is such a politics that will transform the world, and art galleries (when divorced from their dedication to commercial fetishism and presenting a depoliticized aesthetics of the 1%) can play an integral role in the formation of political engagement and creative thinking—the ingredients of world-making, or cosmopolitics, to which Rights of Nature connects.

Lastly, what are the issues that you discuss and analyse in your forthcoming book, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology? When will the book be available

The book—available from Sternberg Press in later 2015—broadly investigates how concern for ecological crisis has entered the field of contemporary art and visual culture in recent years. While ecology has received little systematic attention within art history (not surprising, given its longstanding basis in humanism), ecology’s visibility and significance has only grown worldwide in relation to the pressing threats of climate change, global warming and the environmental destruction of ecosystems. To address these imperatives, this book considers creative proposals from speculative realist and new materialist philosophy, Indigenous cosmopolitics, climate justice activism, and Earth law as critical resources for how to model just forms of life that bring together ecological sustainability, postcapitalist politics, and radical democracy, at a time when those proposals are needed more than ever. By engaging artists’ widespread aesthetic and political engagement of environmental conditions and processes, and doing so in relation to an expansive global scope of investigations—looking at developments in the global South as much as the North—this book offers what I hope will be a significant contribution to the intersecting fields of art history, ecology, visual culture, geography, and environmental politics.

Decolonizing Nature is organized both thematically (with chapters that critically address subjects such as climate refugees, the politics of sustainability, the financialization of nature, and contemporary catastrophism) and geographically (with additional chapters or sections dedicated to Mexico, India, the Arctic, and small island nations like the Maldives, in addition to the US and Europe). Even so, the material has proved so complex that I think of the book now as an introduction to future research. Now that I’ve moved to University of California Santa Cruz, I’ll be able to pursue this work more directly than in London, and I’ll also direct the Center for Creative Ecologies at UCSC, which proposes to offer a platform from which to consider the intersection of culture and environment. The aim is to formulate research tools with which to examine how cultural practitioners—filmmakers, new media strategists, photojournalists, architects, writers, activists, and interdisciplinary theorists—critically address and creatively negotiate environmental concerns. These concerns include anthropogenic climate change and global warming, and relate to factors such as habitat destruction, drought, species extinction, and environmental degradation. Drawing on such wide-ranging fields as political ecology and degrowth economics, Earth jurisprudence and new materialism philosophy, Indigenous cosmologies and climate justice, the Center intends to create a place for the formation of the emerging environmental arts and humanities. But it’s quite early days, and you’ll need to check back in a year or so to see where we’re at!

Marcos Avila Forero, A Tarapoto, Un Manati, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Dohyang Lee, Paris.

---

The artists included in this exhibition are: Allora & Calzadilla, Eduardo Abaroa, Ala Plástica, Darren Almond, Marcos Avila Forero, Amy Balkin, Subhankar Banerjee, Mabe Bethônico, Ursula Biemann & Paulo Tavares, Center for Land Use Interpretation, Minerva Cuevas, Jimmie Durham, Harun Farocki, GIAP: Grupo de Investigación en Arte y Política (with Beatriz Aurora), Paulo Nazareth, The Otolith Group, Fernando Palma Rodríguez, Claire Pentecost, Abel Rodríguez, Miguel Angel Rojas, Walter Solón Romero.

The images are from Nottingham Contemporary and the artists.

Notes:

[1] Winoa Laduke, interviewed by Paul Schmelzer, How the Land Lies: Omaa aikiing in Land, Art: Ecology Handbook

[2] Anselm Jeppe, World of Matter http://www.worldofmatter.net/mineral-exploitation-i#path=mineral-exploitation-i

[3] Klimafestivalen, Norway, December 2014– January 2015 http://klimafestivalen112.no/grunnlovens-§112/

---

Follow the writer TJ Demos online at UCSC UCSC

Listen to the discussion at Demos' book launch at The Showroom here.