Jennifer Crouch in the Arctic Circle: maker, teacher & scientist on researching indigenous navigation, 'tree maps' & plastic pollution in the Arctic with Making in Transit

[18/5/17]

Making in Transit is an exhibition by the artist Jennifer Crouch as a result of her voyage to the remote archipelago of Svalbard, as member of the Arctic Circle Residency Autumn expedition, in 2016. The project extends to a cross-disciplinary programme of free events held at The Cube in London, which has taken on the subjects of mapping, navigation and our relationships to land, sea and the vulnerable Arctic environment. Worm speaks to Jennifer to find out more!

Hello Jennifer, let’s begin with your journey to Svalbard with the Arctic Circle Residency. What had you been researching in your practice before and throughout the trip that reiterated the Arctic environment as significant to your work? Whilst there, did you encounter Arctic ecotourism and what are your views on this?

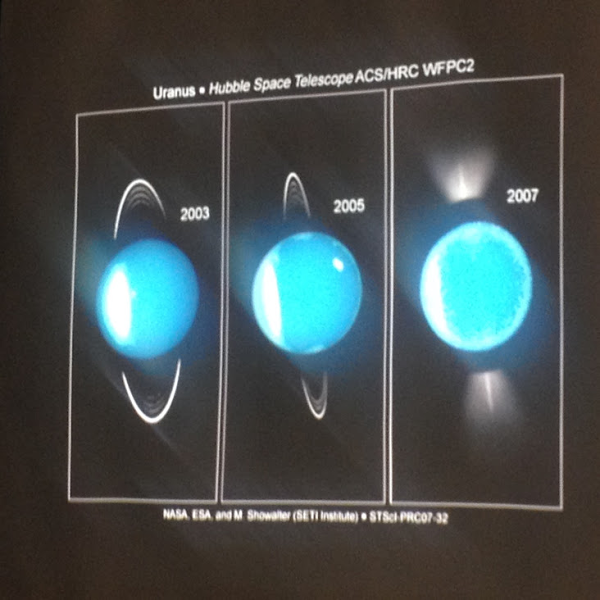

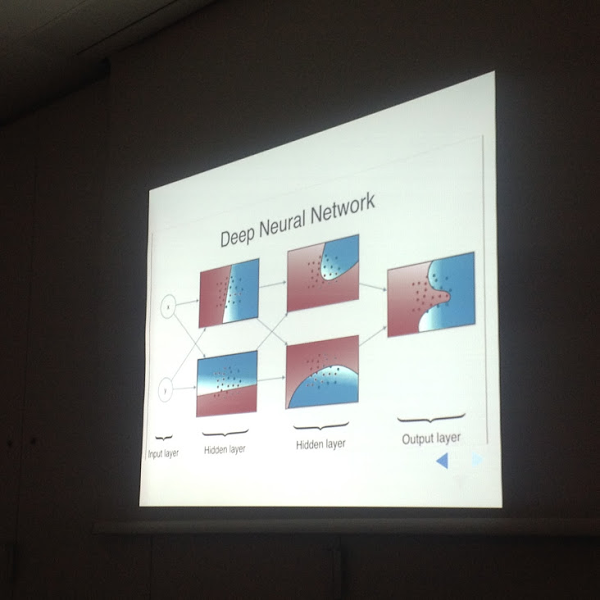

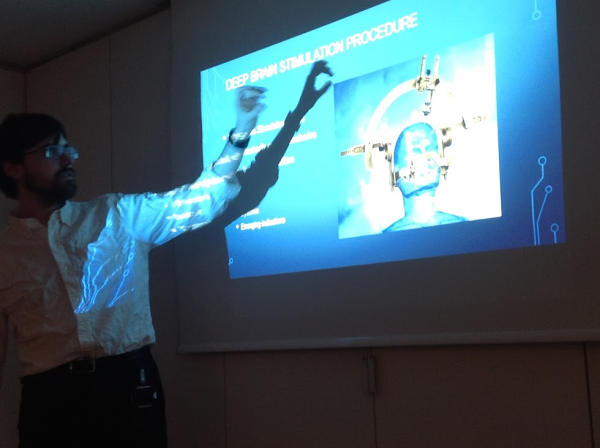

Before I left my research was really varied, focusing on indigenous methods of navigation and sourcing the range of speakers that would talk at the Making in Transit seminars that would take place alongside the exhibition at The Cube. I organised meetings with potential contributors where we discussed what subjects we could explore during the seminars. The experts I spoke to researched subjects such as: navigation, the origins of farming, artificial intelligence, material life-cycles, the anthropology of design, nanotechnology, historical uses of clay, geochemistry, human emotions, architecture, gut bacteria, Arctic ecosystems, biomedical imaging research, and the social dynamics of working environments - the common thread being that we are humans, that we make or invent stuff and that by virtue of doing so we alter our environment.

While I was in the Arctic I focused on indigenous navigation, in particular I worked on hand-carving wooden tactile maps based on designs known as ‘tree maps’ originating from Ammassalik in Eastern Greenland. These maps were invented by Inuit communities and carved out of wood. While a great deal of ambiguity surrounds the maps I've seen online and in museums (dating from around the 1840’s) they are a type of map that can be created in transit in response to observations of one’s environment - and Making in response to the environment is at the heart of this project. These tree maps are a linear representation of coastlines and are useful devices if you happen to be traveling in a small boat, in low light because you can ‘feel your way’ along the map and the coast. The process of making them was very interesting, it required an observation of the landscape and a deep consideration of what needed to be simplified in order for the maps to be functional i.e. representational of the environment in a way that corresponded to the physical distances between places. Selecting which major landmarks such as: bays, mountains, glaciers and rivers to include needed to be ‘the obvious choice’ i.e. something big or significant in the landscape, visible throughout the year, which would have an impact on the perspective of someone in a small boat. But what is interesting is that there is a degree of subjectivity in this choice in a seasonally changing environment - particularly for Svalbard as it’s losing so much ice at the moment. Selecting the scale of the map however was more objective as the tree maps fit into your hand and for each archipelago: what you feel is as far as you can see on a clear day. Compared to the landscape, human hands are roughly the same size and with use, the maps provide a form of tactile knowledge of the landscape. Familiarity and understanding can emerge through the maps’ production and use.

Carving ‘Tree Maps’

Jennifer carving maps - photo by JP, taken in Longyearbyen

Jennifer’s collection of Tree Maps of the NorthWestern Archipelago of Svalbard

Regarding ecotourism I'm on the fence about it. Most of the work available in Svalbard is either ecotourism or science. Almost everyone's job supports the industry. Arguable the residency itself falls under this category regardless of the nature of the work of the people taking part in it. Done with responsibility I think ecotourism can be positive as it can provide an experience of nature that motivates an emotional drive to protect it. Emotion comes before intellect! On the other hand, tourists don't really belong in the immense Arctic wilderness.

The tall ship Antigua, the home of the residency in October 2016

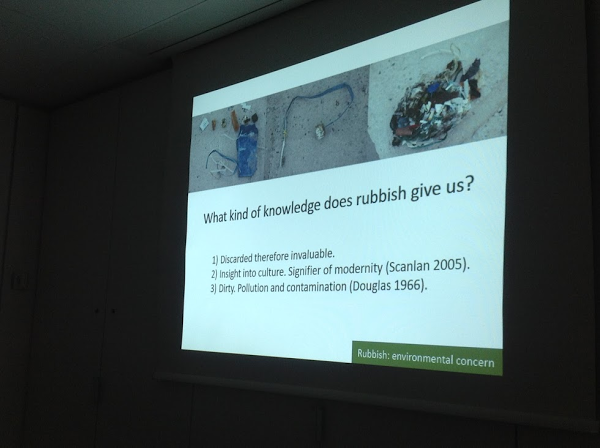

There is an overwhelming amount of tiny fragments of visible plastic at certain points in the Arctic, much of this rubbish has been thrown over the side of ships. Arctic Ecotourism is tightly controlled, and actually there is a greater threat from ordinary or large scale cruise ships and industrial vessels going about their business over the North Atlantic, North Sea and beyond.

Marshlands in Smeerenbergfjorden in the far North West of Svalbard

Plastic thrown over the sides of boats pollute the seas. Ground up by the sea, and washed up during high tides, they can be found in the most remote coastlines of Svalbard.

There are really strict rules about what you can and can't do in the Arctic and for good reason, and you can't just wander around on your own without a guide or you'll probably die or mess something up. The Arctic is a beautiful, hard, indifferent environment. We are not adapted to it. So on the other hand ecotourism is terrible as it disturbs the environment and offers a false vision and idea that we can dominate over nature. So while it's a wonderful place to be, ecotourism has the potential to support the commonly held human delusion that we above all other species can stomp all over the world as we please and profit for the privilege of doing so.

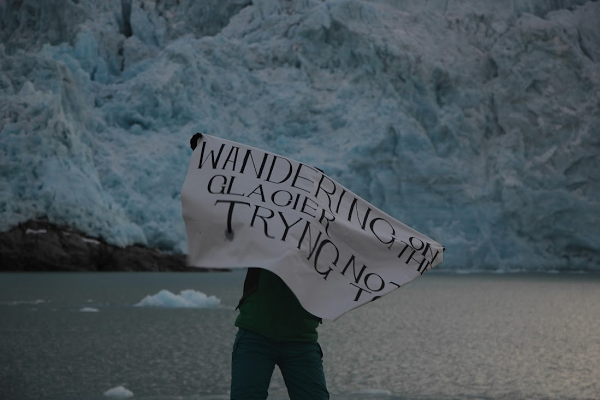

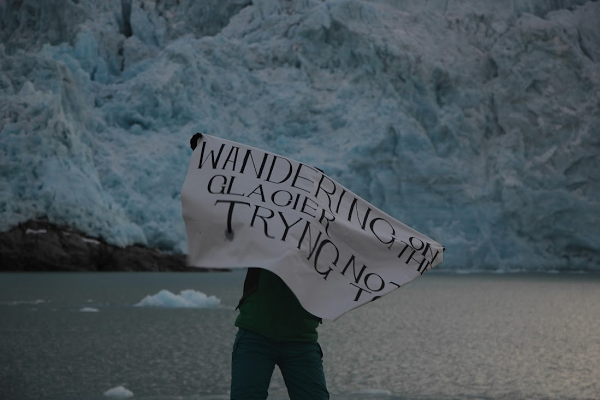

Wandering on the Glacier Trying Not to Die - hand painted sign made by Jennifer in the Arctic

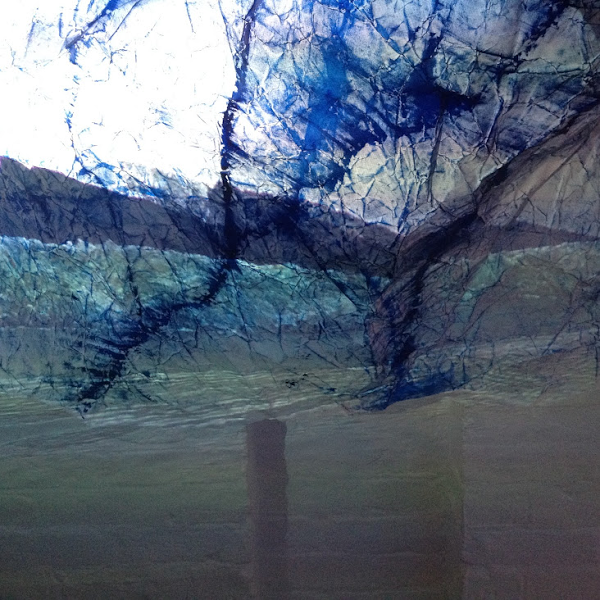

Paintings of the sea created by Jennifer in the London studio

Making in Transit has hosted numerous events with interdisciplinary experts that engage the public with a geography that most will never have a chance to travel to. What have been the most challenging and successful aspects of this ambition?

The main challenge of this project is that I work as a full-time secondary school (high school) teacher. Teaching is a hard job, with strict deadlines, masses of administration, and literally communicating with hundreds of people over the duration of a week. Most of all, teachers have a great deal of responsibility ensuring their students have a well rounded positive, thorough and inspiring education with opportunities for creativity and exploration. I consider it a great privilege working with so many diverse individuals (teachers and students) in an inner-city, non fee-paying, multi-faith school. It's inspiring but challenging. I'm exhausted but there's no other way for me to get everything done that I want to do. So balancing everything (especially considering that my grant application was rejected) has been challenging and successful. It was a huge culture shock coming back and having to get on with work.

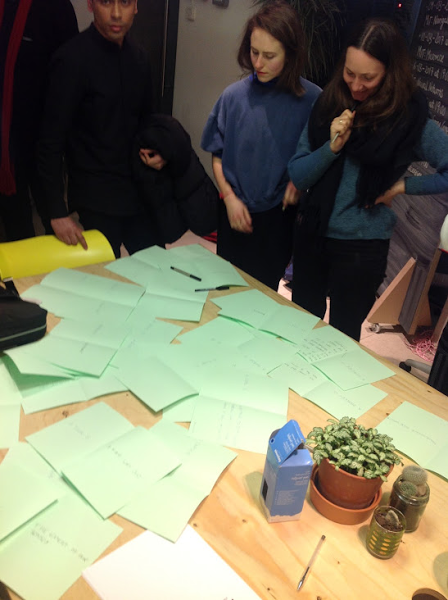

The Making in Transit seminar time-table during the four month exhibition at The Cube.

Regarding the events themselves, the range of experts that spoke at the Making in Transit exhibition and seminars didn’t only talk about The Arctic, it was a much broader range of subject as mentioned before. The talks relate to: human behaviour, our relationship to the environment and to each other, human practices surrounding both why and how we make things. The professors, researchers, poets and artists who spoke at the event and agreed to take part for sake of it - or for the joy of learning and sharing,

Projection of the Making in Transit website showing some of the guest speakers who contributed to the seminars.

The residency was challenging, as the social dynamic on the boat was so interesting - at times jarring with the magnificence of the Arctic landscape. It's cold, wet and uncomfortable and exciting. It's impossible to wonder off on your own without dying unless you have the proper training, experience and knowledge. We would ask our project leader Sarah ‘where are we going today?’ and she would say ‘it depends on the wind’, then we would ask about the weather and she would say ‘I don’t know, we’ll see what happens’. There is just no way of knowing out there. My cabin mate (Jamie Lee Mohr) was telling me that it's just like how in some of the northern beaches in Iceland there are no coast guards - because there's no point. A tourist might ask 'why aren't there any coast guards' but the locals know that you just don't go in the water because the waves are dangerous. That's one of the dangers of ecotourism actually, people do not understand that nature is merciless.

The sterility of city life cuts it off from us off from it and while surviving in a city presents its own challenges, most of us only experience real wilderness via documentaries or images. It's interesting because pictures present a vision or idea of a place that is at odds with corporeal experience and being present in such a place i.e. getting sweaty hiking up a mountain and not being able to shower for two weeks because water must be rationed when at sea.

The Antigua - home in the Arctic

With a strong emphasis on material, such as clay and ice, how has the project evolved materially and about material since returning from the Arctic?

The maps I made were the beginning of the project, and signify a starting point in reflecting on human practices that involve making things. Ice is a material worth contemplating as its familiar, floats, cover 60% of Svalbard and in small amounts can melt in our hands - and ice melting in large quantities is a problem for everyone on the planet.

This project was always going to have materials at the core. So it's not so much that the topic of material evolved, I planned the project to be this way but the discourse sounding each material or process is what evolved through our discussions. This is something that I am still trying to make sense of. Making and the transformation of materials is a really interesting human practice. Material process and furthering our understanding of them, is knowledge that we encoder by making. Every human society makes things, transforming the material in their environment into precious items and tools. It’s what defines us as a species - but it does not mean that we own nature, or that it is moral to exploit it, or assume we are above it, even if our productivity and apt for survival makes makes us feel invincible.

We make to solve problems, to decorate, celebrate and for the sake of it - this is what an opposable thumb and large frontal lobe will do to a species! Everything from bespoke or traditional craft practices to industrial-scale mass-produced poundshop disposable items which are nothing more than instant trash are made, and while they come from the imagination this is mainly thanks to the thumb. Materials are ‘the sugar-phosphate backbone’ of this project and the transformation of materials is both the source of many current environmental and social issues but it also offers the solution.

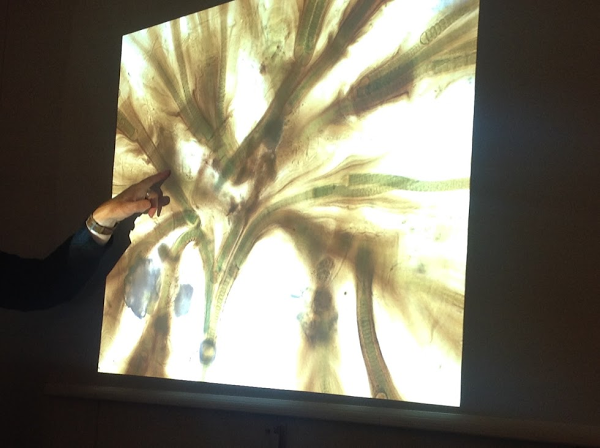

Textures and details of ice and rock - photography by Jennifer Crouch

You investigate the ‘relationships between making and knowledge creation’, specifically methods of crafting tools that are indigenous to the Arctic populations. What was your process in gathering this knowledge as a visitor and what does it mean to have travelled to the Arctic in order to be a knowledge communicator in London?

What the Arctic environment holds in terms of beauty is matched by its ferocity, that's why you need experts to get around there. Indigenous Arctic communities are experts of this environment so researching their knowledge seemed obvious. The next Arctic research trip will have to be to Greenland!

The process of gathering knowledge in Svalbard was the process of making the maps. As mentioned above there's a lot of ambiguity about the original Ammassalik tree maps and it might be the case that they were made to sell to tourists of the 1840’s. But what's wonderful about them is how they connect nature to ourselves through observation and making. There isn't any information about their construction and that is freely available so it was a matter of reverse engineering and interpretation - but this is an artistic project. The maps act as a direct response to nature, grounded in observation. So there is no escape from experience of reality, but there's the creative recording of an area through making.

What's interesting is that there is no indigenous population of humans in Svalbard (or Spitsbergen) the first people to live on Svalbard/Spitsbergen were Norwegian and Dutch whalers in the 17th century so it's interesting to imitate/recreate an Inuit technology in another region of the Arctic circle. The map-carving process is what could be regarded as tacit knowledge. Just like riding a bike, playing the piano or driving a car - it's almost like your body knows how to do it. Tacit knowledge and theoretical knowledge should always be considered together. The thing I like about tacit knowledge is that it can experienced through the senses.

The velvety foothills of Longyearbyen - photography by Jennifer Crouch

How will Making in Transit traverse beyond the exhibition and events, and continue to discuss the endangerment of the Arctic region, its animals, people and cultures?

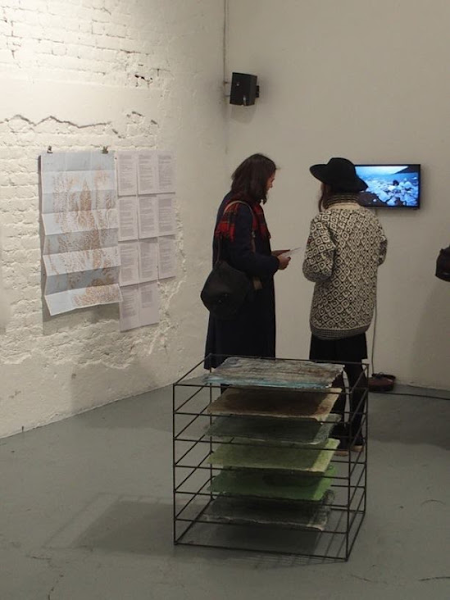

First of all, Making in Transit isn’t just about the Arctic, it’s where the project began and where it returns to. The point is to expand polar research and issues into a global, everyday context. We've collaborated with the UK Polar Network and will continue to do so. Second of all, we will further explore ‘Making’ and how that is having an impact on the environment globally - including further discussion of the Antarctic. To develop the conversations we have had thus far even further, Making In Transit will create a publication (perhaps a book or a series of zines) that collates all the talks, discussions and events held at The Cube between December 2016 and March 2017. This publication will also archive the Arctic expedition. But it's equally relevant to organise a section of the website that archives recordings of the talks themselves with links to further reading, images and other references - this way all the content I want to include in the book is available freely to everyone online. I'm trying to develop Making in Transit into a resource. I'll have to crowd source the publication and website. Making in Transit has also exhibited as part of the Art Science MA project ‘Tracing Wastelands’, and exhibited an Arctic Installation at Lumen Studios in Bethnal Green, carried out workshops with primary school children in an educational context and at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford so I’ve tried to spread it around in places other than London and The Cube.

In December 2017 there will be another series of talks, with more meetings, workshops and discussion. More conversations and inclusion of all people - all welcome, all free - that's our tag-line for every event. We are anti-exclusive at Making in Transit, anti-glamour, non-corporate and want to keep it that way. We want to make expertise accessible without making people feel intimidated or like they are ‘not smart enough’ to get involved, without over simplifying or compromising any details of expertise. I’ll be going back to Svalbard in the next four years - I'm aiming for a 2018 trip but that depends on work. Something else I am very interested in investigating in the long term are the Marshall Islands stick charts so I hope to investigate those - through making and observing the sea.

All photographs and photo captions are provided by Jennifer Crouch.

---

Follow Jennifer Crouch and Making in Transit:

Website: www.makingintransit.com

Facebook: @MakingInTransit

Instagram: @jennifer.crouch

Twitter: @JenniferCrouch

Making in Transit is an exhibition by the artist Jennifer Crouch as a result of her voyage to the remote archipelago of Svalbard, as member of the Arctic Circle Residency Autumn expedition, in 2016. The project extends to a cross-disciplinary programme of free events held at The Cube in London, which has taken on the subjects of mapping, navigation and our relationships to land, sea and the vulnerable Arctic environment. Worm speaks to Jennifer to find out more!

Hello Jennifer, let’s begin with your journey to Svalbard with the Arctic Circle Residency. What had you been researching in your practice before and throughout the trip that reiterated the Arctic environment as significant to your work? Whilst there, did you encounter Arctic ecotourism and what are your views on this?

Before I left my research was really varied, focusing on indigenous methods of navigation and sourcing the range of speakers that would talk at the Making in Transit seminars that would take place alongside the exhibition at The Cube. I organised meetings with potential contributors where we discussed what subjects we could explore during the seminars. The experts I spoke to researched subjects such as: navigation, the origins of farming, artificial intelligence, material life-cycles, the anthropology of design, nanotechnology, historical uses of clay, geochemistry, human emotions, architecture, gut bacteria, Arctic ecosystems, biomedical imaging research, and the social dynamics of working environments - the common thread being that we are humans, that we make or invent stuff and that by virtue of doing so we alter our environment.

While I was in the Arctic I focused on indigenous navigation, in particular I worked on hand-carving wooden tactile maps based on designs known as ‘tree maps’ originating from Ammassalik in Eastern Greenland. These maps were invented by Inuit communities and carved out of wood. While a great deal of ambiguity surrounds the maps I've seen online and in museums (dating from around the 1840’s) they are a type of map that can be created in transit in response to observations of one’s environment - and Making in response to the environment is at the heart of this project. These tree maps are a linear representation of coastlines and are useful devices if you happen to be traveling in a small boat, in low light because you can ‘feel your way’ along the map and the coast. The process of making them was very interesting, it required an observation of the landscape and a deep consideration of what needed to be simplified in order for the maps to be functional i.e. representational of the environment in a way that corresponded to the physical distances between places. Selecting which major landmarks such as: bays, mountains, glaciers and rivers to include needed to be ‘the obvious choice’ i.e. something big or significant in the landscape, visible throughout the year, which would have an impact on the perspective of someone in a small boat. But what is interesting is that there is a degree of subjectivity in this choice in a seasonally changing environment - particularly for Svalbard as it’s losing so much ice at the moment. Selecting the scale of the map however was more objective as the tree maps fit into your hand and for each archipelago: what you feel is as far as you can see on a clear day. Compared to the landscape, human hands are roughly the same size and with use, the maps provide a form of tactile knowledge of the landscape. Familiarity and understanding can emerge through the maps’ production and use.

Carving ‘Tree Maps’

Jennifer carving maps - photo by JP, taken in Longyearbyen

Jennifer’s collection of Tree Maps of the NorthWestern Archipelago of Svalbard

Regarding ecotourism I'm on the fence about it. Most of the work available in Svalbard is either ecotourism or science. Almost everyone's job supports the industry. Arguable the residency itself falls under this category regardless of the nature of the work of the people taking part in it. Done with responsibility I think ecotourism can be positive as it can provide an experience of nature that motivates an emotional drive to protect it. Emotion comes before intellect! On the other hand, tourists don't really belong in the immense Arctic wilderness.

The tall ship Antigua, the home of the residency in October 2016

There is an overwhelming amount of tiny fragments of visible plastic at certain points in the Arctic, much of this rubbish has been thrown over the side of ships. Arctic Ecotourism is tightly controlled, and actually there is a greater threat from ordinary or large scale cruise ships and industrial vessels going about their business over the North Atlantic, North Sea and beyond.

Marshlands in Smeerenbergfjorden in the far North West of Svalbard

Plastic thrown over the sides of boats pollute the seas. Ground up by the sea, and washed up during high tides, they can be found in the most remote coastlines of Svalbard.

There are really strict rules about what you can and can't do in the Arctic and for good reason, and you can't just wander around on your own without a guide or you'll probably die or mess something up. The Arctic is a beautiful, hard, indifferent environment. We are not adapted to it. So on the other hand ecotourism is terrible as it disturbs the environment and offers a false vision and idea that we can dominate over nature. So while it's a wonderful place to be, ecotourism has the potential to support the commonly held human delusion that we above all other species can stomp all over the world as we please and profit for the privilege of doing so.

Wandering on the Glacier Trying Not to Die - hand painted sign made by Jennifer in the Arctic

Paintings of the sea created by Jennifer in the London studio

Making in Transit has hosted numerous events with interdisciplinary experts that engage the public with a geography that most will never have a chance to travel to. What have been the most challenging and successful aspects of this ambition?

The main challenge of this project is that I work as a full-time secondary school (high school) teacher. Teaching is a hard job, with strict deadlines, masses of administration, and literally communicating with hundreds of people over the duration of a week. Most of all, teachers have a great deal of responsibility ensuring their students have a well rounded positive, thorough and inspiring education with opportunities for creativity and exploration. I consider it a great privilege working with so many diverse individuals (teachers and students) in an inner-city, non fee-paying, multi-faith school. It's inspiring but challenging. I'm exhausted but there's no other way for me to get everything done that I want to do. So balancing everything (especially considering that my grant application was rejected) has been challenging and successful. It was a huge culture shock coming back and having to get on with work.

The Making in Transit seminar time-table during the four month exhibition at The Cube.

Regarding the events themselves, the range of experts that spoke at the Making in Transit exhibition and seminars didn’t only talk about The Arctic, it was a much broader range of subject as mentioned before. The talks relate to: human behaviour, our relationship to the environment and to each other, human practices surrounding both why and how we make things. The professors, researchers, poets and artists who spoke at the event and agreed to take part for sake of it - or for the joy of learning and sharing,

Projection of the Making in Transit website showing some of the guest speakers who contributed to the seminars.

The residency was challenging, as the social dynamic on the boat was so interesting - at times jarring with the magnificence of the Arctic landscape. It's cold, wet and uncomfortable and exciting. It's impossible to wonder off on your own without dying unless you have the proper training, experience and knowledge. We would ask our project leader Sarah ‘where are we going today?’ and she would say ‘it depends on the wind’, then we would ask about the weather and she would say ‘I don’t know, we’ll see what happens’. There is just no way of knowing out there. My cabin mate (Jamie Lee Mohr) was telling me that it's just like how in some of the northern beaches in Iceland there are no coast guards - because there's no point. A tourist might ask 'why aren't there any coast guards' but the locals know that you just don't go in the water because the waves are dangerous. That's one of the dangers of ecotourism actually, people do not understand that nature is merciless.

The sterility of city life cuts it off from us off from it and while surviving in a city presents its own challenges, most of us only experience real wilderness via documentaries or images. It's interesting because pictures present a vision or idea of a place that is at odds with corporeal experience and being present in such a place i.e. getting sweaty hiking up a mountain and not being able to shower for two weeks because water must be rationed when at sea.

The Antigua - home in the Arctic

With a strong emphasis on material, such as clay and ice, how has the project evolved materially and about material since returning from the Arctic?

The maps I made were the beginning of the project, and signify a starting point in reflecting on human practices that involve making things. Ice is a material worth contemplating as its familiar, floats, cover 60% of Svalbard and in small amounts can melt in our hands - and ice melting in large quantities is a problem for everyone on the planet.

This project was always going to have materials at the core. So it's not so much that the topic of material evolved, I planned the project to be this way but the discourse sounding each material or process is what evolved through our discussions. This is something that I am still trying to make sense of. Making and the transformation of materials is a really interesting human practice. Material process and furthering our understanding of them, is knowledge that we encoder by making. Every human society makes things, transforming the material in their environment into precious items and tools. It’s what defines us as a species - but it does not mean that we own nature, or that it is moral to exploit it, or assume we are above it, even if our productivity and apt for survival makes makes us feel invincible.

We make to solve problems, to decorate, celebrate and for the sake of it - this is what an opposable thumb and large frontal lobe will do to a species! Everything from bespoke or traditional craft practices to industrial-scale mass-produced poundshop disposable items which are nothing more than instant trash are made, and while they come from the imagination this is mainly thanks to the thumb. Materials are ‘the sugar-phosphate backbone’ of this project and the transformation of materials is both the source of many current environmental and social issues but it also offers the solution.

Textures and details of ice and rock - photography by Jennifer Crouch

You investigate the ‘relationships between making and knowledge creation’, specifically methods of crafting tools that are indigenous to the Arctic populations. What was your process in gathering this knowledge as a visitor and what does it mean to have travelled to the Arctic in order to be a knowledge communicator in London?

What the Arctic environment holds in terms of beauty is matched by its ferocity, that's why you need experts to get around there. Indigenous Arctic communities are experts of this environment so researching their knowledge seemed obvious. The next Arctic research trip will have to be to Greenland!

The process of gathering knowledge in Svalbard was the process of making the maps. As mentioned above there's a lot of ambiguity about the original Ammassalik tree maps and it might be the case that they were made to sell to tourists of the 1840’s. But what's wonderful about them is how they connect nature to ourselves through observation and making. There isn't any information about their construction and that is freely available so it was a matter of reverse engineering and interpretation - but this is an artistic project. The maps act as a direct response to nature, grounded in observation. So there is no escape from experience of reality, but there's the creative recording of an area through making.

What's interesting is that there is no indigenous population of humans in Svalbard (or Spitsbergen) the first people to live on Svalbard/Spitsbergen were Norwegian and Dutch whalers in the 17th century so it's interesting to imitate/recreate an Inuit technology in another region of the Arctic circle. The map-carving process is what could be regarded as tacit knowledge. Just like riding a bike, playing the piano or driving a car - it's almost like your body knows how to do it. Tacit knowledge and theoretical knowledge should always be considered together. The thing I like about tacit knowledge is that it can experienced through the senses.

The velvety foothills of Longyearbyen - photography by Jennifer Crouch

How will Making in Transit traverse beyond the exhibition and events, and continue to discuss the endangerment of the Arctic region, its animals, people and cultures?

First of all, Making in Transit isn’t just about the Arctic, it’s where the project began and where it returns to. The point is to expand polar research and issues into a global, everyday context. We've collaborated with the UK Polar Network and will continue to do so. Second of all, we will further explore ‘Making’ and how that is having an impact on the environment globally - including further discussion of the Antarctic. To develop the conversations we have had thus far even further, Making In Transit will create a publication (perhaps a book or a series of zines) that collates all the talks, discussions and events held at The Cube between December 2016 and March 2017. This publication will also archive the Arctic expedition. But it's equally relevant to organise a section of the website that archives recordings of the talks themselves with links to further reading, images and other references - this way all the content I want to include in the book is available freely to everyone online. I'm trying to develop Making in Transit into a resource. I'll have to crowd source the publication and website. Making in Transit has also exhibited as part of the Art Science MA project ‘Tracing Wastelands’, and exhibited an Arctic Installation at Lumen Studios in Bethnal Green, carried out workshops with primary school children in an educational context and at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford so I’ve tried to spread it around in places other than London and The Cube.

In December 2017 there will be another series of talks, with more meetings, workshops and discussion. More conversations and inclusion of all people - all welcome, all free - that's our tag-line for every event. We are anti-exclusive at Making in Transit, anti-glamour, non-corporate and want to keep it that way. We want to make expertise accessible without making people feel intimidated or like they are ‘not smart enough’ to get involved, without over simplifying or compromising any details of expertise. I’ll be going back to Svalbard in the next four years - I'm aiming for a 2018 trip but that depends on work. Something else I am very interested in investigating in the long term are the Marshall Islands stick charts so I hope to investigate those - through making and observing the sea.

All photographs and photo captions are provided by Jennifer Crouch.

---

Follow Jennifer Crouch and Making in Transit:

Website: www.makingintransit.com

Facebook: @MakingInTransit

Instagram: @jennifer.crouch

Twitter: @JenniferCrouch